What does it mean to offer sacrifice? What is its aim and end? These are questions about which there is a great deal of misunderstanding. As Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger has recently observed, “[t]he common view is that sacrifice has something to do with destruction,” that is, it has to do with the destruction of some material thing withdrawn from man’s use so as to bear witness to God’s sovereignty.1 Though not without a grain of truth, this view is partial and obscures the real impetus of the notion. Moreover, when Ratzinger goes on to conclude that the essence of sacrifice is deification, the partial notion may leave the reader scratching his head: where did Ratzinger get this counter-intuitive idea?

I will explore this rich notion of sacrifice—richer than the “common view” of which Cardinal Ratzinger speaks—by first outlining Ratzinger’s theology of sacrifice found in his seminal work The Spirit of the Liturgy. Then I will draw out the concept of sacrifice from its traditional roots in St. Augustine’s The City of God. Lastly, I will briefly show the light this revised notion of sacrifice sheds on the most important concrete instantiations of sacrifice in the Christian economy, namely: Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross; the Eucharistic sacrifice; and, lastly, the Christian sacrifice of self.

Ratzinger, Augustine, and the Fire of Love

In the course of The Spirit of the Liturgy, Ratzinger inevitably confronts one of the key questions that lies at the center of human existence: “What,” he asks, “is worship? What happens when we worship?”2 It is in this context that Ratzinger introduces the subject of sacrifice. He begins by outlining the destructive formulation noted above, asking how God can be honored by man surrendering something for the purpose of destruction. One answer to this question “is that the destruction [i.e. of the sacrificial gift] always conceals within itself the act of acknowledging God’s sovereignty over all things.”3 Though Ratzinger does not say as much, this statement is a likely reference to the position of Cardinal John De Lugo (1583-1660), for whom sacrifice as worship of God required that our life be destroyed (as represented in the gift offered) as a protestation of God’s sovereignty.4

Against this conception, Ratzinger counters that the kind of surrender God wants is something altogether different. He wants to be honored, not by surrender unto destruction, but by surrender that terminates in the union of man with God. True sacrificial surrender, he writes, consists “in the union of man and creation with God.”5 Sacrifice thus has to do with a new “way of being” toward God, a way called love. 6 This is the reason, Ratzinger avers, “St. Augustine could say that the true ‘sacrifice’ is the civitas Dei, that is, love-transformed mankind, the divinization of creation and the surrender of all things to God.”7 Thus, on Ratzinger’s account, the goal of sacrifice is simply the honoring of God by the man transformed through union with God, re-ordered to God by means of divine charity.

In this passage, Ratzinger is working quickly, like a math student who gets the right answer without showing his work. Nevertheless, his allusion to St. Augustine tells us where he is coming from. Though not explicitly cited, it is clear that Ratzinger is referring to Augustine’s The City of God, x.6, one of the great loci classici of sacrificial discussions in the Christian West. Let us turn to this important passage of Augustine.

Augustine begins his discussion in x.5 by making a distinction between the exterior sacrifice (offered in the public cult) and the interior sacrifice (the offering of oneself to God in the human heart). The relationship between them is one of sign to thing signified.8 It is this latter sacrifice—the interior sacrifice—that is the primary locus of Augustine’s discussion in x.6. The exterior sacrifice, also present here, is that of a work pressed into the service of this interior sacrifice.

In x.6, Augustine begins his argument by affirming that true sacrifice is every work which is done that we may be united to God in holy fellowship, and which has a reference to that supreme good and end in which alone we can be truly blessed.”9 In this passage, Augustine affirms that the goal of sacrifice—that which motivates its offering—is desire for union with God. As such, it is a work done with reference to our ultimate end, namely, beatitude. If a work is not directed to God for this end (i.e., is not referred to God so that we might be rightly ordered to him) thereby achieving blessedness, it is not a sacrifice. Sacrifice is, at bottom, a consecration, a process through which, true, a man dies to himself, but so that he may live before God.10 In this process, Augustine tells us, the body becomes a sacrifice “when we chasten it by temperance,” so that we can present our members as “instruments of righteousness unto God.”11 Thus if the body, though “inferior” to the soul, can become a sacrifice when it is pressed into service to God, this is all the more true of the soul.12 And how does the soul become a sacrifice? For Augustine, it becomes a sacrifice “when it offers itself to God, in order that, being inflamed by igne amoris eius, the fire of his love, it may receive of his beauty and become pleasing to him, losing the shape of earthly desire, and being remoulded in the image of permanent loveliness.”13 Here we see Augustine’s stress on sacrifice as deification come to the fore. For, ultimately, what it means for a man to become a sacrifice before God is that he himself is refashioned in the divine image through ignis amoris, the fire of love; in the process, his soul becomes beautiful as it partakes of God’s beauty. Sacrifice here is a dynamic movement where, true, a man dies to himself and to all selfishness as he chastens his body with its disordered passions through temperance; all the while, however, his soul is refashioned by divine charity, through which he is united with his end, the Good.

In this way, Christ, through his sacrificial death, leads men to God through the conferral of grace, so as to make of men sons of God and members of his body, that they might live for God and, indeed, in God. It is in this context that Augustine’s text occurs, which Ratzinger alluded to above. Augustine sums up his idea as follows: “thus, the whole redeemed city, that is to say, the congregation or community of the saints, is offered to God as our sacrifice through the great High Priest, who offered Himself to God in his passion for us, that we might be members of this glorious head.”14 Or, again, he writes: “This is the sacrifice of Christians: we, being many, are one body in Christ,”15 for, ultimately, it is in him and through his agency that we offer ourselves that we might be united to God through so great a Head.

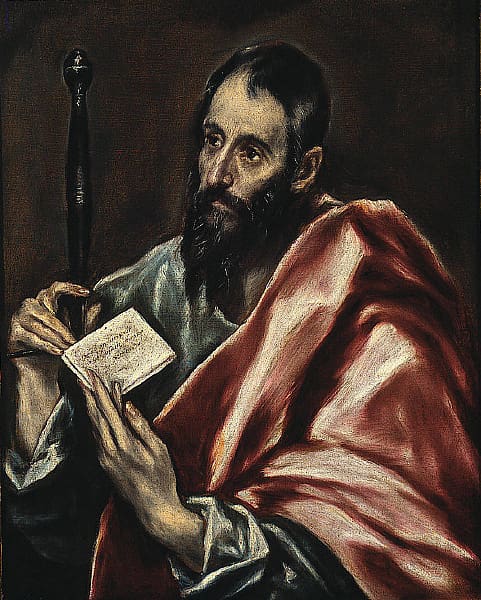

To sum up: for Ratzinger and, before him Augustine, a sacrifice is any work by which we are rightly ordered to and are united with God as our end, that we might live in blessed communion with him. As such, the aim of sacrifice is to honor God through the perfective transformation of one’s life, so reordered by grace. Moreover, if there be a destructive moment in this process— when, for example, a man dies to himself—this is always pressed into service to a higher end, namely: deification, union with God through the body of the God-man, Jesus Christ. Or, as St. Paul said of himself: “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.”16

Application to the Sacrifices of the New Covenant

Focusing on this theory of sacrifice as a point of departure, I would now like to take the remainder of this essay to show how this idea of sacrifice allows us to rethink and broaden our understanding of sacrifice in the New Testament. Let us first turn to the sacrifice of Christ as it is developed, in particular, by the German dogmatician Matthias Scheeben (1835-1888).

Over a century ago, Scheeben revisited Augustine’s concept of sacrifice17 and translated it into a theology of sacrifice that, taking its sensible baseline from Israel’s public temple worship, shifted the focus from the sacrificial slaughter as such to the relationship of the slaughter to the ritual burning of the gift in the altar fire. What this meant for Scheeben is that, broadly speaking, there are two moments in the rite of sacrifice, the renunciatory moment, but also the further moment of union with God, the first being ordered to the second. This second moment—the moment of union—was typified in Israel’s worship through the burning of the victim in the altar fire, an action that Scheeben viewed as not primarily destructive, but as perfective, the consumption through fire signifying God’s acceptance of the gift into his own communion of life.18 This being the case, the renunciation present in the slaughter is ordered to union with God, and it finds its sacrificial worth as an expression of the offerer’s desire to attain to said union.19

When Scheeben goes on to apply this two-part schema to Christ, he arrives at a conception of Christ’s redemptive activity which, in the 20th century at least, will be called the Paschal Mystery, that is, the unity of Cross and Resurrection in Christ’s one sacrifice. On this conception, if Christ’s death on the cross for the sins of the world corresponds to the renunciatory moment in sacrifice (the slaughter of animals in the Old Testament), then Christ’s resurrection and ascension correspond to the divine acceptance of the gift and its total entry into God (the consumption by divine fire). “But we must insist on the fact,” Scheeben writes, that Christ’s “resurrection and ascension actually achieve in mystically real fashion what is symbolized in the sacrifice of animals by the burning of the victim’s flesh.”20 As such, Christ’s sacrifice terminates in his “Resurrection and glorification,” where, consumed “by the fire of the Godhead,” the slain Lamb is caused “to ascend to God in lovely fragrance as a holocaust [the Old Testament burnt offering], there to make it, as it were, dissolve and merge into God.”21 Thus the term of Christ’s sacrifice is the total deification, on the one hand, of his own humanity (lacking from the first in terms of its outward expression on account of his voluntarily assumed kenotic Incarnation), and, on the other, of the deification of the sons of Adam for whom he died so as to liberate them from their sins (impediments to deification). And, not coincidentally, when Scheeben seeks to elucidate the traditional ground of this transformative view of divine fire in resurrection, he does so with copious patristic references, chief among these, St. Augustine.22

If in the preceding Scheeben presented the acceptation and total deification of Christ’s sacrifice (and ours) as accomplished in its acceptation in Resurrection— what we might call deifying sacrifice as final eschatology—nevertheless he also doubles back and reapplies it to Christ’s activity in his kenotic state as well, above all in his Passion—what we might call deifying sacrifice as realized eschatology (the “now-but-notyet” of the Christian economy). Here, the altar fire is at work in a hidden fashion, proleptically or by way of anticipation, in Christ’s charity, through which he offered himself on the Cross. In this way, viewed from the inside out, Scheeben actually considers even Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross to be, not so much a sacrifice accomplished through Schlachtung, slaughter; instead, he considers the sacrifice on the Cross itself to be an Auflösung, a dissolution accomplished from within through fire, that is, through the power of Christ’s charity, and, indeed, “the fire of the eternal spirit.”23 Thus, for Scheeben, the Passion too is a kind of burnt offering, a gift transformed through divine fire. Moreover, with this image of the interior dynamism of Christ’s charity leading him to surrender himself in order to bring men to God, we are once again very close to Ratzinger’s and Augustine’s conceptual formulations of sacrifice. God is glorified when men are rightly ordered to him, in this life and in the consummation of the age to come.

What about the Eucharist? Where does the Eucharist fit into this re-ordering of human beings to God? We already saw, in St. Augustine, how the sacrifice of Christians is their incorporation into and union with Christ’s body so as to become his living temple, living because Christ lives in them. But this too, in Augustine’s words, “is the sacrifice which the Church continually celebrates in the sacrament of the altar”—that is, in the Eucharist, the sacrifice of the body of Christ—“in which she teaches that she herself is offered in the offering she makes to God.”24 The Eucharist is the body of Christ that we offer and to which we are united in its offering and which, especially in communion, further fortifies our union with Christ’s body. For, as Scheeben puts it, it is this very flesh which “pour[s] forth the consuming fire of love into our souls.” Moreover, “[i]t is from this flesh that we are to draw the strength to offer up our souls to God; and in union with that flesh, which reposes on the bosom of the Godhead, we are to lay our souls as a worthy and sweet-smelling sacrifice before the throne of God.”25

As to the Christian sacrifice of self, this too is accomplished, as we already saw in Augustine, when we are rightly ordered, or, as the case may be, re-ordered to God. This re-ordering happens, on the one hand, when we chasten our body, with its sinful passions, through temperance, but above all, when the soul donates itself to God, becoming transformed and ennobled with his beauty in the process. In this life, this transformation takes the form of dying to self so as to rise to God, a whole offering transformed through the fire of grace and charity. And when this life is done? Then we will become a perfect burnt offering, completely transformed and assimilated to God by the fire of glory. Or, in Scheeben’s words: “By the immolation of their bodies and their earthly life, effected in all the sufferings, mortifications, and toils of this life and crowned in death, by the immolation which takes place in Christ’s members in the spirit and power of Christ, the members are made ready as a fragrant holocaust…. After the general resurrection the whole Christ, head and body, will be a perfect holocaust offered to God for all eternity… through the transforming fire of the Holy Spirit.”26

Concluding Remarks In Called to Communion, Ratzinger sums up his account of Christian priesthood by simply noting: “The ultimate end of all New Testament liturgy and of all priestly ministry is to make the world as a whole a temple and a sacrificial offering for God.”27 Through our survey of Ratzinger’s reflections and their Augustinian foundations, we have seen why this is the case, and, indeed, how the terms “temple” and “sacrificial offering” are in this passage practically synonymous. For the term of sacrifice is the surrender and, through surrender, right ordering of creation to God for the purpose of union with God through the body of the God-man, so that it might be deified and become his living temple. In Ratzinger’s words: “the goal of worship and the goal of creation as a whole are one and the same—divinization, a world of freedom and love.”28 Deification: this is the end of man as he becomes a living sacrifice, consumed by the deifying fire of the Holy Spirit, a gift imparted through the redeeming death of the Savior, the God-man, Jesus Christ. These ideas, reappropriated so recently by Ratzinger, are, I submit, fertile ground for further exploration so as to move deification back to its rightful place, into the very center of Christian theology. After all, it is for this deification that we were made: to glorify God through union with him, God living his life in us, and we, our lives in him.

David L. Augustine is currently a doctoral candidate in the Systematic Theology program at Catholic University of America. He is the research assistant to Drs. Matthew Levering and Reinhard Hütter. He is a recent graduate of the Liturgical Institute at Mundelein Seminary, where he earned an MALS (Master of Arts Liturgical Studies).

1. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. John Saward (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 27.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., 28.

4. See John de Lugo, De sacramento Eucharistiae, disp. 19, set. 1, n.

5. in Opera 4 (Venetiis: Sumptibus Nicolai Pezzana, 1718), 330. For an English translation and discussion, see Maurice de la Taille, The Mystery of Faith, Book I: The Sacrifice of Our Lord (New York & London: Sheed & Ward, 1940), 1n1. For a related discussion, see Matthias Scheeben, Handbuch der Katholischen Dogmatik, vol. V/2, 2nd ed., ed. Carl Feckes, in Gesammelte Schriften, vol. VI/2, ed. Josef Höfer (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1954), n. 1424. (All citations from Scheeben’s Handbuch follow paragraph rather than page numbers). De Lugo’s view was widely disseminated in the theology manuals of the pre-conciliar era.

5. Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, 28.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Augustine, The City of God, trans. Marcus Dods (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2006), x.5 (p. 370): “And the fact that the ancient church offered animal sacrifices, which the people of God now-a-days reads of without imitating, proves nothing else than this, that those sacrifices signified the things which we do for the purpose of drawing near to God, and inducing our neighbour to do the same. A sacrifice, therefore, is the visible sacrament or sacred sign of an invisible sacrifice.”

9. Ibid., x. 6 (p. 371), emphases added.

10. Cf. Ibid. x. 6 (p. 371-72): “Thus man himself, consecrated in the name of God, and vowed to God, is a sacrifice in so far as he dies to the world that he may live to God.”

11. Ibid. x. 6 (p. 372). Augustine’s scriptural allusion in this passage is to Rom 6:19.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid. The Latin has been inserted from St. Augustine, De Civitate Dei, Bk. XXII, vol. 1, Bks I-XIII, ed. Emanuel Hoffman, in Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, vol. 40 (Vindobonae: F. Tempsky, 1899), 454-55.

14. St. Augustine, The City of God, x. 6 (p. 372).

15. Ibid., x. 6 (p. 373).

16. Gal 2:20, Revised Standard Version, 2nd Catholic edition, emphasis added.

17. Although he was also influenced by Thomas Aquinas, as he was too by the 17th century French priestly reform movement known collectively as the French School.

18. See esp. Handbuch V/2, nn. 1425, 1439-40.

19. Cf. Handbuch V/2, n. 1424: “Every act of submissiveness and renunciation has a sacrificial tendency precisely insofar as it aims, directly or indirectly, to introduce the offerer into a state wherein he lives wholly in God and for God and precisely through this finds his own beatitude.” (All translations from Scheeben’s Dogmatics are my own.) The conceptual similarity here with Augustine and Ratzinger is striking

20. Matthias Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, trans. Cyril Vollert (New York: Crossroad, 2006), 436.

21. Ibid.

22. See ibid., 436n6, and esp. 439n9.

23. Scheeben, Handbuch V/2, n. 1478. (The translation is my own.)

24. Augustine, The City of God x. 6 (p. 373).

25. Scheeben, The Mysteries, 521.

26. Ibid., 439.

27. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Called to Communion: Understanding the Church Today, trans. Adrian Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1996), 127.

28. Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, 28.