By Jeremy Priest

Signs of the Holy One, by Uwe Michael Lang. Ignatius Press (San Francisco 2015), 180 pp., $17.95.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then how much is a symbol worth?

Father Uwe Michael Lang seeks to answer this question – among others – in his reflections in Signs of the Holy One. The book is an expansive meditation on the assertion that the “‘non-verbal symbols’” in the Church’s liturgy are “more significant than language itself.” Signs of the Holy One is certainly a fitting sequel to his last offering, The Voice of the Church at Prayer (Ignatius, 2012), where Lang focused on issues surrounding the intersection of language and liturgy.

Worship and Beauty

Signs focuses on two basic sets of questions that arise from a couple observations: Firstly, he notes, the Church’s solemn public worship speaks through a variety of ‘languages’ other than language in the literal sense” (9); secondly, the discussion of beauty “in the context of modernity…has been reduced to a subjective judgment,” he writes, particularly beauty’s application to the languages of art and architecture. These observations lead Lang to explore questions regarding the nature of “the attribute ‘sacred’” (Chapter 1); “what makes the liturgy sacred” (Chapter 2); how the “sacred” is embodied in Church architecture (Chapter 3); how the concept of beauty can be established theologically (Chapter 4); how the sacrality of Church music can lead us out of the present crisis (Chapter 5); and finally how the establishment of Summorum Pontificum can be a path of real liturgical renewal (Epilogue).

The notion of the sacred has enormous importance for Christianity. Indeed, if the sense of the sacred is lost in society “‘the hand with which man is able to grasp what is authentically Christian threatens to wither’” (17, quoting Josef Pieper). In Chapter 1, Lang begins by using the tools of social anthropology and ritual studies to understand the notion of the sacred and how it works in relation to symbol and ritual. While reviewing the contributions of such students of ritual as Emile Durkheim, Rudolph Otto, Mircea Eliade, Arnold van Gennep, and Clifford James Geertz, Lang sides with the work of a pioneer of ritual studies, Victor Turner. Quoting Turner, Lang shows the realm of the sacred is the “liminal,” the actuality of “‘being-on-a-threshold,’ where the participants ‘cease to be bounded by the secular structures of their own age and confront eternity which is equidistant from all ages’” (37).

Crossing this threshold opens the way into a ritual world ‘“of symbols and ideas’” where “even persons who are profoundly separated from one another in the ordinary world, ‘cooperate closely’” and transcend ‘the contradictions and conflicts inherent in the mundane social system’” (37-38). For Turner, the ritual world “of symbols and ideas” functions as an exemplar where the real cosmic order encountered in the liminal world or the ritual “allows its participants to integrate their experience of the human condition into” their everyday lives (38). In this way, liminality has its own “time and space,” which are set apart from the everyday. These forms may seem “archaic,” or even obsolete, but can (because they do not come from the ordinary), create a sacred world in which the everyday world is impacted.

Sacred Liturgy

Lang takes these anthropological insights concerning ritual, symbol, and the sacred into Chapter 2, asking “What makes the liturgy sacred?” Lang begins by questioning the pervasive view of theologians Karl Rahner and Edward Schillebeeckx who call the very concept of “sacred” into question. In their “vision the whole created world is regarded as already endowed with or permeated by divine grace” (44), and the nature-grace distinction is blurred by making categorical revelation merely an explication of what is already in man. So, for Rahner, “the sacraments constitute the manifestation of the holiness and the redeemed state of the secular dimension of human life and of the world.” Such signs are merely visible indicators that “this entire world belongs to God” already (45). Thus, Sacraments are not understood as “causes of grace extra nos but, rather as visible manifestations of the inner event of grace that is already taking place in man and in the world and is not necessarily linked with Christian revelation” (46).

In responding to Rahner’s and Schillebeeckx’s critiques, Lang notes that “sacredness” is always understood to be “derived from the liturgy, which is the presence and action of Christ in his Mystical Body” (56, cf. SC 7). Lang’s response hinges on the notion of sacramentality and the distinction Ratzinger makes between the “already” and the “not yet”: “This is the time of the Church, which is an intermediate state between ‘already’ and ‘not yet.’ In this state, the ‘empirical conditions of life in this world are still in force,’ and for this reason the distinction between the sacred and the quotidian still hold, even if this distinction is not conceived of as an absolute separation” (61). Expressed in the Church’s use of elements to give solemnitas to ritual actions that “are distinguished by a stupendous humility and simplicity” (58), the sacramentality of the liturgy, shows forth the liminal reality of the sacraments that effect “a change or transformation in those who participate in” them (23): what is visible is clothed in glory to point toward the invisible.

Building Holiness

If sacramentality points the way to the sacred in the liturgy, Chapter 3 asks how this “renewed conception of the sacred can be translated into the design and construction of buildings dedicated to the liturgy” (71). After founding the ontology of the church building upon “Christ’s Body, in both its ecclesiological and its Eucharistic dimension” (81), Lang offers four “linguistic” principles of architectural language that help to communicate a sense of the sacred: verticality, orientation, thresholds, and the intrinsic connection between art and architecture.

Lang summarizes the power of the first two principles: “The orientation of liturgical space, combined with the first principle of verticality, reaches beyond the visible altar toward eschatological fulfillment, which is anticipated in the celebration of the Holy Eucharist as a participation in the heavenly liturgy and a pledge of future glory in the presence of the living God. The cosmic symbolism of facing east also recalls that the liturgy ‘represents more than the coming together of a more or less large circle of people: the liturgy is celebrated in the expanse of the cosmos, encompassing creation and history at the same time’ and so reminds us ‘that the Redeemer to whom we pray is also the Creator.’” (87)

The third principle is the need to not merely have entry ways or doors, but to have real “thresholds.” Lang names two such thresholds. The first, the entrance of the church, is not merely an organized hole through which people enter the building, but rather a portal through which people, by an act of faith, cross into the Lord’s House. The second threshold is between the nave and the sanctuary, where heaven and earth meet.

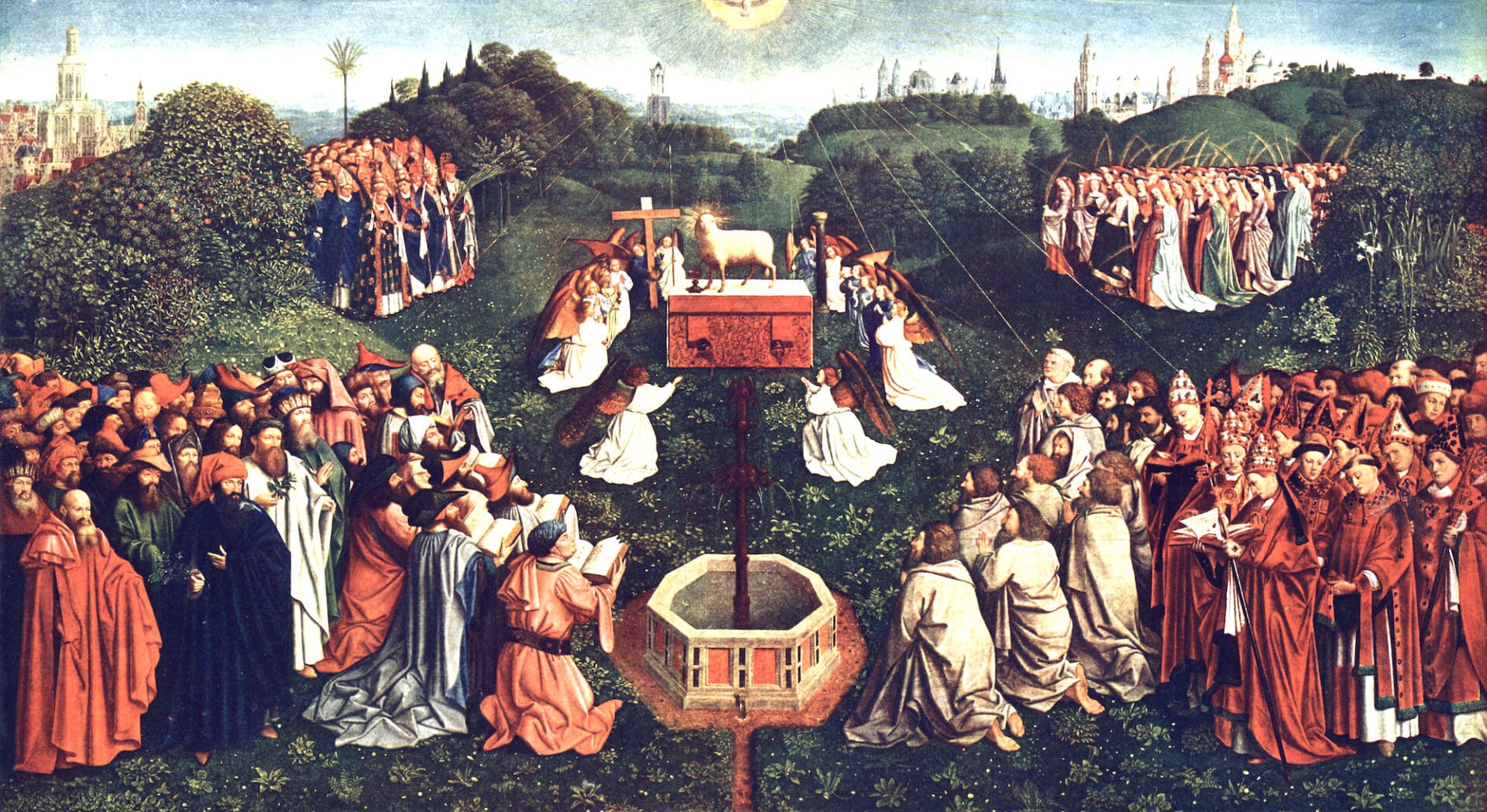

In establishing the fourth principle. Lang sees the intrinsic connection between sacred art and architecture. Since “God has acted in history and entered into our sensible world,” beautiful images, “in which the mystery of the invisible God becomes visible, are an essential part of Christian worship. . . . Iconoclasm is not a Christian option” (89, quoting Ratzinger). These images are essentially figurative without being purely naturalistic, nor being pure abstractions.

Modern Questions

In Chapter 4, Lang gives a theological response to modernity regarding the concept of sacred art. Of note here is Lang’s commentary on SC 123’s liberty for a variety of forms. Rather than the Church’s rich variety of styles being a license for an artistic free-for-all, the creativity of forms given in SC 123 has, Lang argues, “always existed within certain coordinates” (110). These coordinates, Lang proposes, can be located in Pius XII’s assertion that new forms should be capable of joining their voices to the already existing “wonderful choir of praise” (MD 195).

Thus, a “hermeneutic of continuity” can be discerned not only between Pius XII and Vatican II, but more precisely between the sacred art and architecture that went before and that which is presently being produced. Lang contextualizes this continuity again by citing the 1917 Code of Canon Law, where it “stipulated that Ordinaries, that is, above all diocesan bishops, should take care that, when a new church had to be built or an existing one had to be renovated, ‘the forms received from Christian tradition and the laws of sacred art are preserved’” (114, CIC 1164§1). The artistic tradition of East and West makes clear that any “renewal of the Church’s architectural and artistic expressions must retain visible continuity with those that have been received” (116).

Sounds of Music

Offering a “brief historical overview,” Chapter 5 shows how “the contemporary problems concerning sacred music are not new” (15). Lang gives no quarter to the area of sacred music, describing the contemporary situation as a choice between two millstones (functionalism unqualified and a functionalism of accommodation) threatening to grind up the sacred liturgy into powder. After an historical overview of how these issues have plagued the Church over the centuries and the ways in which Joseph Ratzinger has contributed to the postconciliar discussion (both as theologian and then as pope), Lang offers several practical considerations that may help negotiate a path between these millstones. Of them, the most salient is his lament regarding the “widespread replacement of the Proper chants of the Roman Mass with other ‘apt’ or ‘congruous’ forms of music, as permitted by the General Instruction of the Roman Missal” (148).

While these other options are certainly permissible, “music is often of low quality, influenced by pop culture, and is hardly appropriate for the sacred liturgy” (148). Quoting chant scholar Laszlo Dobszay, Lang argues that the “disappearance of the Gregorian Propers ‘means that the Church today no longer speaks through the chants of the Mass: that the chants effectively have no part at all in forming the liturgy and delivering its message.’ The intimate connection between liturgy and music is severed” (148). Parishes may very well sing hymns that are appropriate to the season, but the way the Church has arranged the liturgical texts to correspond to seasons and rites fails to be reproduced in the selection of hymns. The musical tone of the season is of course joyful, but an interior joy. “All too often, however, the general influence of consumerist society affects the celebration of the liturgy, so that Christmas is unduly anticipated, while Advent loses its proper character. Music has an important role in shaping the liturgical year, and the Gregorian chant repertory is exemplary in this regard” (149).

Rites in Time

In the book’s Epilogue, Lang comments on the possibility of liturgical renewal and the dangers of ritual change. A genuine way forward would be impeded and perceived as “another rupture” if traditional forms were simply decreed. Pope Benedict’s move toward reform in issuing Summorum Pontificum was to allow these two very distinct ritual forms to coexist and to allow the gravitas of the usus antiquior to influence the ordinary form, while the Extroardinary Form could legitimately adopt some new possibilities. If this “mutual enrichment” works the way it was conceived, then “the characteristic spirit or ethos informing the ritual expression of the sacred” would be “essentially the same” (154) and thus create a situation where we could genuinely “speak of two forms of the same rite” (155).

Signs of the Holy One gives much to reflect on with regard to the nature of the liturgy, particularly its sacred character and how that is expressed through signs. Attention to the “hermeneutic of continuity” with regard to all of the liturgical signs (from the vessels to the church building) can help us to establish the “symbolic world” of the liturgy, so that its rituals have more room to effect the “change or transformation” the Lord intended through the sacraments (23). This involves paying attention to the principle of sacramentality and the accompanying solemnitas given to the relatively simple actions of the liturgy.

While building and renovating churches is not an everyday practice, Father Lang gives much to think about in terms of how aspects of the church building are emphasized. For example, I know of many churches where the main “threshold” entrance is often never used, even for ritual occasions. Is there a threshold into the sanctuary? Is the sacred art in our churches a hodgepodge of things thrown together, or do they tend toward the “wonderful choir of praise” (MD 195) spoken of by Pius XII? Does the Church’s first and preferential option for sacred music get due consideration in the selection of sacred music employed in the liturgy? Father Uwe Michael Lang shows himself a sure guide as he moves from liturgical theology into ritual theory, from sacramental theology to sacred art and architecture, from liturgical music to principles of liturgical reform. In all of these, Lang manages to not only be informative, but insightful and thought provoking.

Jeremy Priest holds BAs in Theology and Philosophy. He studied graduate theology and scripture at the Pontifical College Josephinum and is currently finishing up his STL (focus in Sacramental Theology) at the Liturgical Institute of the University of St. Mary of the Lake.