Imagine yourself walking along the Jordan River one afternoon. As you pass by a man dressed in camel’s hair, you see him point into the distance and say, “Behold, the Lamb of God!” Would it surprise or confuse you, especially if you were a devout member of the Chosen People? Calling someone a “Lamb of God” is a strange thing to do – isn’t it?

Or imagine yourself today, just prior to the reception of Holy Communion, singing a short litany about the “Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.” And then, as if to emphasize the point, the priest raises the host and says, echoing John the Baptist, “Behold, the Lamb of God!” Is the appellation “Lamb of God” any less strange now than it may have been 2000 years ago?

For a follower of John the Baptist, reference to the Lamb of God would not, I submit, have been an odd one to make, for the Chosen People’s history had seen many lambs. For a follower of Jesus, his title “Lamb of God” should also not be peculiar, and for the same reasons that John’s disciples didn’t find it peculiar.

But perhaps we’ve become accustomed to hearing of Jesus as Lamb of God and, like any familiar part of life, have not stopped to listen “with the ear of the heart.” How can we hear with greater acuity and grasp more firmly the meaning of the “Lamb of God”?

In one of its most insightful sections, the Catechism of the Catholic Church reveals how to uncover the meaning of the liturgy’s signs and symbols – and words. “A sacramental celebration,” it says early on in Part II, “is woven from signs and symbols. In keeping with the divine pedagogy of salvation, their meaning is rooted in the work of creation and in human culture, specified by the events of the Old Covenant and fully revealed in the person and work of Christ” (CCC 1145). These signs also “prefigure and anticipate the glory of heaven” (CCC 1152).

True, “Lamb of God” means Jesus. But if we wish to hear how it means Jesus, and the depth and detail and meaning and mystery of the expression, then looking to its roots, as the Catechism says, in creation, in culture, in the Old Covenant, in the life of Christ, and in heaven will help the words to resound more fully in our ears.

Creation

“Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow.” The color of the newborn lamb (well, of most lambs) is dazzling white, as was Jesus’ own clothing at the Transfiguration (Lk 9:29). The lamb is gentle and obedient: get one accustomed to your voice (as at feeding time) and he will – by natural instinct – come when called. Beginning March 21, the date of the spring equinox and the beginning of spring, the constellation Aries – The Ram – shines the lamb over the earth. Thus, from nature, the lamb means purity, gentleness, obedience, and new life. In short, it means Jesus.

Culture

“Culture” is the root (no pun intended) of agriculture, and for much of history and in many places around the world the lamb has been a staple of farming. As the winter comes to an end in the northern hemisphere, and the natural world reawakens, planters and farmers and gardeners also get busy. Ewes bred in the late fall begin to deliver lambs near the end of March. It is believed that early nomadic herders, at the birth of the first springtime lamb, would offer it as a thanksgiving sacrifice to the gods. Here, cult, culture, and agriculture come together, cooperate, and grow. The lamb, from the cultural standpoint, signifies stewardship, thanksgiving, and sustenance, much in the same way that Jesus signifies these things as the Lamb of God.

Old Testament

Lambs and rams and sheep abound in the story of the Chosen People. Abel offered a “firstling from the flock” and, in a sense, is himself sacrificed. Isaac – after approaching Mt. Moriah on donkey, carrying the wood of the sacrifice up the mountain on his shoulders, submitting to his father’s will–is redeemed and replaced by a ram, whose horns were caught in a tree or thicket. (It was the springtime of the year, incidentally, with Aries itself looking on.) The firstborn in Egypt were likewise ransomed by an unblemished lamb, the “Paschal Lamb,” the blood of which marked the houses of the Israelites. Isaiah also spoke of the “lamb led to the slaughter or a sheep before the shearers, [who] was silent and opened not his mouth…. [T]hrough his suffering, my servant shall justify many, and their guilt he shall bear” (Isaiah 53:7, 11). The lambs of the Old Covenant, and to which John referred, represent willing sacrifice and life-giving redemption. These types of lambs find fulfillment in history’s greatest lamb, Jesus.

Christ

At the beginning of Jesus’ public ministry, John not only calls Jesus the Lamb of God, but identifies him further as that Lamb “who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). At the end of Christ’s public ministry, the Paschal Lamb of God offered himself. Whereas the synoptic Gospels locate Jesus’ death on the day after Passover, the Gospel of John recounts Jesus’ death on the “preparation day for Passover, about noon” (John 19:14), the time when the annual slaughter of the Paschal Lambs began in the Temple. Jesus is the definitive lamb, the one for which all other lambs had been preparing, the one which, after his sacrifice on Calvary, all lambs will recall.

Heaven

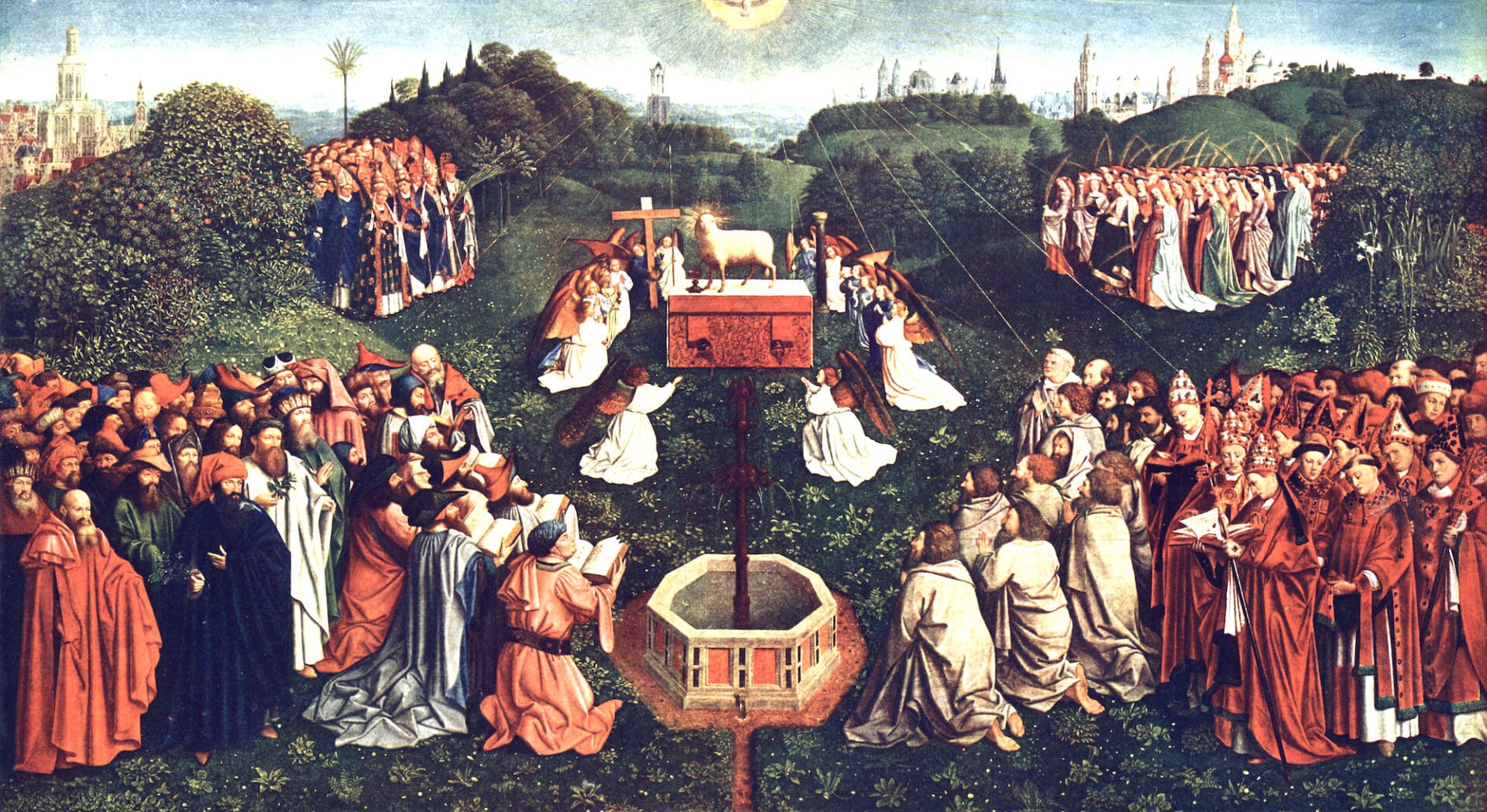

The death of the Lamb on Calvary, of course, was not the end. Heaven depicts “a Lamb that seemed to have been slain” (Revelation 5:6). The Lamb, although slain, is standing: it is a victorious Lamb, one enthroned, powerful, worthy, and worshipped. Heaven itself is likened to a wedding feast – of the Lamb. “The wedding feast of the Lamb has come, his bride has made herself ready…. Blessed are those who have been called to the wedding feast of the Lamb” (Revelation 19:7-9). Heaven, the last-named source of liturgical meaning, symbolizes a celebrating lamb, victorious and life-giving.

Ecce Agnus Dei!

Behold, then, this “Lamb of God” whom we hear of in the liturgy, whom we worship and receive and emulate. How should we describe him? This Lamb is pure, gentle, obedient, alive and life-giving, man’s collaborator, a sign of thanksgiving, sacrificial, redeeming, humble, suffering, atoning, victorious, a bridegroom, and the source of eternal life.

We have heard of (and maybe even heard) lambs before. The next time we hear “Behold, the Lamb of God” at Mass, may we recognize a Lamb unlike any other. Jesus, the Lamb, knows his sheep: do we know ours?