Online Edition

August 2014

Vol. XX, No. 5

A Medievalist Considers Inculturation in the Sacred Art

©2014 Daniel Mitsui

by Daniel Mitsui

Early in 2010, a priest commissioned me to draw Saint Michael in the style of a Japanese woodblock print. At the time, I had little knowledge of East Asian art, despite having some Japanese ancestors. My strongest artistic influence was (and remains) the religious art of medieval Europe. My patrons soon began requesting other transpositions of Catholic iconography into the idiom of ukiyo-e.

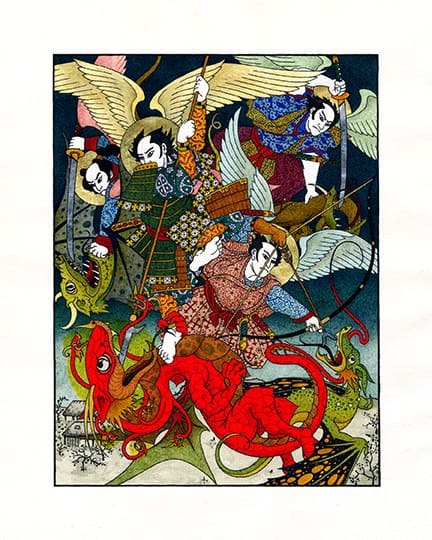

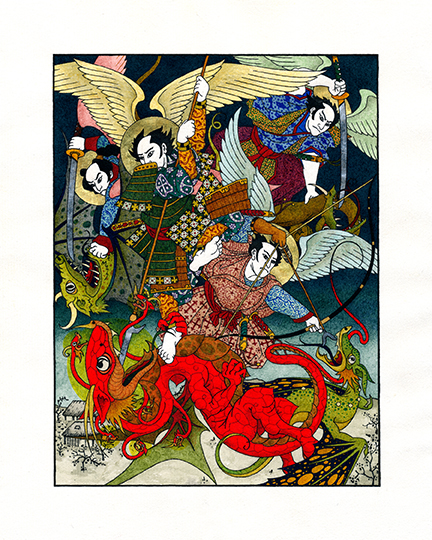

I enjoyed drawing Our Lady of Perpetual Help with a halo of lotus leaves, Saint Raphael in the robes of a samurai, and the Wedding at Cana with patristic commentaries illustrated on saké pots and folding screens. In the work shown here, I revisited the subject of Saint Michael, borrowing the composition from Albrecht Dürer’s 1498 Apocalypse woodcuts and the style from Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s prints of legendary heroes battling monsters.

The ingenious composition, brilliant color, and lively rendering displayed in these prints convinced me that they ranked among the greatest works of art; I began to borrow elements from them in drawings that were not explicitly styled on Japanese art. The hybridizing of medieval European and Japanese imagery had become no mere experiment, but an important part of my artistry.

Being dedicated to the preservation and revival of medieval tradition, my guiding principle had long been the instruction of the Second Nicene Council:

The composition of religious imagery is not left to the initiative of artists, but is formed upon principles laid down by the Catholic Church and by religious tradition…. The execution alone belongs to the painter; the selection and arrangement of subject belong to the Fathers.1

When making Catholic religious drawings in the Japanese style, I became uncomfortably aware that I was attempting things that had not, to my knowledge, been done before. These drawings were all based on woodblock prints of the ukiyo-e genre, mostly from the late 19th century. Ukiyo-e means floating world. The concept was explained by the 17th-century author Asai Ry?i:

Living only for the moment, turning our full attention to the pleasures of the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms and the maple leaves; singing songs, drinking wine … caring not a whit for the pauperism staring us in the face, refusing to be disheartened … this is what we call the floating world.2

Many prints of this genre depicted courtesans or kabuki actors. Although I was careful to avoid using indecent pictures as artistic models (instead finding historical or literary scenes that resonated with the Biblical narratives), and although I relied on Christian artistic models for the selection and arrangement of subject, I was aware that the idiom of ukiyo-e was one created to glorify transitory pleasure rather than eternal salvation. I wondered if my hybrid drawings were really at all appropriate.

The most obvious principle that might justify such attempts as mine is that of inculturation, which Pius XII defined as:

[T]o facilitate the deeper appreciative insight into the most varied civilizations and to put their spiritual values to account for a living and vital preaching of the Gospel of Christ. All that in such usages and customs is not inseparably bound up with religious errors will always be subject to kindly consideration and, when it is found possible, will be sponsored and developed.3

This idea is not new, and was consciously embraced by Jesuit missionaries to the Far East as early as the 16th century.4 While little artwork has survived from the Japanese missions, the Jesuits in China produced several extant examples of Sinicized religious art, including illustrations for Chinese-language devotional and catechetical texts.5 Such works were visual analogues to Matteo Ricci’s proposal to use Confucianism as the philosophical framework for Chinese Catholicism.

These Jesuits’ strategy of evangelization in the Far East was criticized by missionaries of other religious orders and by contemporary popes who feared that Catholic doctrine was being compromised.6 More recent popes have favored inculturation on principle, but even their endorsement leaves unanswered questions related to my own endeavors.

Is culturally hybrid religious art justified outside of a missionary context? And how tightly binding are the stylistic traditions of earlier religious art? Although currently out of favor, the original opponents of inculturation had a legitimate point: cultural forms are not altogether neutral.

I wondered if there were another principle that might justify such art as I was creating, one that would have been acceptable even to the artists of the Middle Ages. I searched for precedents in their work.

I learned that some scant artwork survives from the medieval Franciscan missions to Yüan Dynasty China. Recently discovered tombstones carved in 14th-century Yangzhou display reliefs of the Last Judgment, the life of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, and the Virgin Mary. The Jesuit scholar Francis Rouleau saw elements of both European and Chinese art in these pictures.7

Surprisingly, I found even more intercultural borrowing in the art of medieval France and Italy. As early as the Merovingian Dynasty, textiles imported from Zoroastrian or Isl?mic nations were used in French Catholic churches for vestments, tapestries, and veils; to cover tombs; and to wrap relics.8 In the 7th century King Dago-bert had precious fabrics hung about the newly built abbey church of St. Denis9; the practice was maintained when Suger was abbot and undertook the renovation of the church that inaugurated the age of Gothic art. A 15th-century panel painting by the Master of St. Giles shows the interior of the same church with such hangings still in use.10

The origin of many of these fabrics in S?s?nid Persia or the Caliphate of Baghdad is evidenced not only by woven text, but by imagery drawn from ancient Middle Eastern mythology. One silk used to wrap the relics of Saint Victor at Sens Cathedral bears the figure of Gilgamesh. These fabrics exercised an influence on other artistic media. The French art historian Emile Mâle identified many of the fantastic animals carved on capitals in Romanesque churches as borrowings from Middle Eastern textiles. Mâle even suggested that the use of these translucent damasks as curtains inspired the invention of stained glass windows.11

The paintings of late medieval Italy similarly borrow from the art of Mamluk Egypt. Kufic letters decorate the trims of the Virgin Mary’s robes in paintings by Ugolino de Nerio and Paolo Veneziano, among others. In the great Adoration of the Magi altarpiece by Gentile da Fabriano, Kufic characters and Isl?mic patterns are punched into the haloes of the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph.12 These haloes are imitations of gold platters made by Egyptian artisans.13

The origin of these textiles and gold vessels outside Christendom did not, in the consideration of these medieval artists, delegitimate them as influences. Why did these artists accept them? Not to appeal to the tastes of Muslims for the sake of evangelization, for their works were placed before the eyes of faithful Catholics residing in the hearts of their own nations. Indeed, the artists showed almost no concern about the original meaning of the influential works. The Kufic lettering found in Italian paintings is almost always gibberish.14

The guiding principle here, as best as I can tell, is the one stated again and again in the writings of Suger of Saint Denis, perhaps most poetically in his justification for the expense of golden altar vessels:

I confess that one thing has always seemed preeminently fitting to me: that every costly or costlier thing should serve, first and foremost, for the administration of the Holy Eucharist…. If, by a new creation, our substance were reformed from the holy Cherubim and Seraphim, it would still offer an insufficient and unworthy service for so great and so ineffable a victim.15

Elsewhere, he extols fine artistry even higher than precious material: “Marvel not at the gold and the expense but at the craftsmanship of the work.”16

In other words, God, because He is God, deserves the very best that we have to offer. The textiles of Mesopotamia and the platters of Egypt were fitting influences on Catholic sacred art because they were the most precious and beautiful things of their kind that medieval Christendom had yet encountered. To eschew them would be something of a cheat on God. Beauty, as Saint Thomas Aquinas teaches, is transcendental; his artistic contemporaries believed that it transcended even the falsehoods professed by its makers.

It is perhaps the key to the genius of Abbot Suger (and the artists of the age that followed him) that they were able to uphold both the principle of traditionalism and the principle of always giving the best and most beautiful to God. Rather than deadening each other, these two impulses together propelled Catholic sacred art to new heights of magnificence, such as the Gothic cathedral.

It is perhaps the key to the revival of the sacred arts in our own time that artists think less of giving the people what they want and more of giving God what He is owed. He is owed fidelity; the teaching of Nicea II must endure. And He is owed our best; in seeking to give form to the old traditions, expressing them in ever richer and more varied ways, nothing truly beautiful is unworthy of consideration.

NOTES:

1 Second Ecumenical Council of Nicea (787). Quoted by Emile Mâle, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the 13th Century, translated by Dora Nussey (New York: Harper & Row, 1958), p. 392.

2 Ukiyo Monogatari (Tales of the Floating World) by Asai Ry?i, (ca 1661). Quoted by Tamara Tjardes, One Hundred Aspects of the Moon: Japanese Woodblock Prints by Yoshitoshi (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003), p. 81.

3 Summi Pontificatus by Pius XII (1939).

4 For example, Il Cerimoniale per i Missionari del Giappone by Alessando Valignano (1581).

5 For example, Songnianzho guicheng (How to Pray the Rosary) by João da Rocha (1619) and Tianzhu jiangsheng chuxiang jingjie (Explanation of the Incarnation and Life of the Lord of Heaven) by Giulio Aleni (1637). Mentioned by Jeremy Clarke, The Virgin Mary and Catholic Identities in Chinese History (Hong Kong University Press, 2013), pp. 42-46.

6 Jeremy Clarke, pp. 60-64.

7 Ibidem, pp. 15-24.

8 Emile Mâle, Religious Art in France of the 12th Century, translated by Marthiel Matthews (Princeton University Press, 1978), pp. 341-344.

9 Gesta Dagoberti (ca 830). Mentioned by Emile Mâle, Religious Art in France of the 12th Century, p. 342.

10 James Snyder, Northern Renaissance Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1985), p. 243.

11 Emile Mâle, Religious Art in France of the 12th Century, p. 345.

12 David Carrier, A World Art History and Its Objects (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008), pp. 15-17.

13 Carole Hillenbrand, Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 2000), p. 406.

14 Carrier, pp. 15-17.

15 Suger of St. Denis, On the Abbey Church of St. Denis and Its Treasures, edited and translated by Erwin Panofsky (Princeton University Press, 1979), pp. 65-67.

16 Ibidem, p. 47.

***

Daniel Mitsui, an editorial consultant to The Adoremus Bulletin, is an artist who specializes in ink drawings and prints and lives in Chicago with his wife, Michelle, and their three children. He attended Dartmouth College, from where he studied drawing, painting, printmaking, and film animation. He is currently working to establish Millefleurs Press, an imprint for publishing fine printed books. In 2011, the Vatican commissioned him to illustrate a new edition of the Roman Pontifical. His work can be seen online at danielmitsui. com.

Adoremus, Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy

*