March 2014

Vol. XX, No. 1

Cardinal George Pell, archbishop of Sydney, Australia since 2001, addressed a symposium observing the 50th anniversary of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium. The symposium, sponsored by the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (CDW) and the Pontifical Council for Culture, was held February 18-20 in Rome, during the consistory of cardinals held the week before Pope Francis elevated 19 prelates to the cardinalate on February 22.

Cardinal Pell’s knowledge of translation issues is extensive. He has been chairman of Vox Clara — the select group of bishops and experts that aids the CDW with the translation of English-language liturgical texts — since it was created in 2001. He is also a member of Pope Francis’s “Council of Eight” cardinal advisors.

On February 24, the pope named Cardinal Pell prefect of a newly created Vatican dicastery, the Secretariat for the Economy, which will oversee Vatican finances.

We are pleased to publish Cardinal Pell’s address to the symposium on Sacrosanctum Concilium — with his kind permission.

I. LITURGICAL TRANSLATIONS

The Age of Translation

In our “global village” today translations play a great part. The supranational bodies such as the European Union and the United Nations Organization battle with the diplomatic and linguistic niceties of ensuring the translation of Thai texts into Estonian, Mongol into Greek, and Maltese into Indonesian. The many channels of Italian television offer — alongside locally produced programs — myriad films and other imported transmissions dubbed expertly into the Italian language. An inexpensive electric torch comes with an instruction sheet in 32 languages. Our computers are equipped with software capable in seconds of translating between many tongues and even reading them aloud.

Naturally, some of these translations are ephemeral, gone on the wind like our everyday casual conversations, but it is a challenge of another higher order to translate Dickens into Polish, Flaubert into Quechua, and Dostoyevsky into English.

We are grateful, of course, for the good people of all Christian denominations, often Protestants, who spend their entire working lives ensuring the translation of the Scriptures into as many languages as possible.

Latin in the Roman Liturgy and the Exceptions

Most of us will know that the first Christian community in Rome was more likely to be familiar with Greek than Latin.1 It was only by the middle of the 3rd century that the official language of the Church of Rome became resolutely Latin. By the time of the pontificate of Saint Damasus (366-384), the Eucharistic Prayer was probably in Latin, though there may have been some persistent bilingualism at a later date.2

Despite this, much later, in the years 638-772, some use of Greek returned to Rome itself with immigration from the East. A remnant of the bilingualism of this period was the repetition of the Epistle and Gospel in Greek on certain occasions,3 a practice employed by the Roman authorities after Trent for meeting liturgical linguistic needs in the missions. Similar measures have been found in great centers of pilgrimage down the long centuries. We know, for example, that the Spanish pilgrim Egeria reports of the Jerusalem liturgy at the turn of the 4th-5th century that after the Greek text, the Syriac was then given for those who had little Greek and that in any case there were interpreters for Syriac and Latin.4 These general procedures were not rare in other regions and in other centuries.5

However, as remarked above, the predominance of Latin in the Liturgy is not in doubt and the evidence for pre-Tridentine Western use of vernacular translations is scarce, as presumably the practice itself, where it existed, was scarce and uneven.6

The clear evidence we have for derogation from the monopoly of Latin in Western use comes from the missions, far and near.

In the age of Marco Polo (1254-1324), Friar John of Montecorvino — later Archbishop of Khanbalik or Beijing (†1328) —celebrated the Roman Mass among the Mongols of Southern Siberia in Öngüt Turkish,7 and another friar missionary, the Dominican Bishop Bartholomew of Bologna (†1333), had the Dominican Missal and Breviary translated into Armenian.8 It seems to me unlikely that these incidents happened solely by personal initiative. That the popes were willing on occasion to give authorizations is clear from the fact that in 1398 and again in 1406 Boniface IX and then Innocent VII authorized the translation of the Dominican Missal into Greek for celebrations at Constantinople.9

The interaction ecclesiologically, politically, and liturgically between Western and Eastern Christendom is fascinating, but their ambition to remain faithful to tradition is the same as ours. It is interesting therefore to note the so-called “Eastern Principle” of the Greek Church, formulated by the Greek Patriarch of Antioch, Theo-dore Balsamon (1185-1195), who wrote: “Those who are wholly orthodox but who are altogether ignorant of the Greek tongue shall celebrate in their own language, provided only that they have exact versions of the customary prayers.”10

Do not let us forget that Greek Catholics in the Italian peninsula and even Orthodox elsewhere knew and used Greek or Old Slavonic translations of parts at least of the Roman Liturgy under such names as the Divine Liturgy of Saint Peter or of Saint Gregory. Many Italian Catholic priests of Greek culture celebrated for their people in Greek, whether in the Byzantine or the Roman Rite, in various parts of southern Italy well into the 19th century. Remember, too, that Italy currently harbors an ancient Greek Catholic monastery at Grottaferrata, and two Byzantine-rite Albanian Catholic dioceses, in Calabria and Sicily.

Another complex historical knot is the use in the Roman Rite of Slav languages, including Old Slavonic, especially in Croatia and Slovenia, a phenomenon that goes back fundamentally to the missions of Saints Cyril and Methodius.11

While Trent, exacerbated by anti- Catholic polemic, hesitated on vernacular translations, and in fact maintained the use of Latin, exceptions continued to be made, though with interesting conditions. Just as we saw the Greek Patriarch of Antioch insisting on “exact versions of the customary prayers,” so too when the Holy Office in 1615 authorized a Chinese translation of the Bible, and of the liturgical books, including the Roman Missal, it specified that the rendering was not to be into “the vulgar but the erudite” tongue.12

The medieval and post-medieval Catholic missions to the Middle East and to other parts of Asia provoked similar requests about translations into Arabic, Persian, Georgian, and Armenian. The responses of the Holy See were varied, nuanced and not infrequently extremely erudite. Remember that during all this period Propaganda Fide [Propagation of the Faith] was printing in Rome on its own presses liturgical books for the various Eastern Catholic Churches,13 a concrete and costly sign of its awareness and respect for the “Eastern Principle” of vernacular liturgy in the East. Until industrial techniques were introduced into the printing trade early in the 19th century, printing had been arduous and expensive. The craftsmen in Rome printing the first edition of the 1570 Missale Romanum of Saint Pius V sweated over it for more than a year. At the same time, what was countenanced for the East was not readily allowed in the West. A proposal in favor of using the vernacular in the liturgy put forward by the Enlightenment Synod of Pistoia of 1786 was rejected firmly by the Holy See.14

The First Half of the Twentieth Century

While some of the missions founded in the 19th century were evangelizing peoples who had no pre-Christian literary heritage, others encountered ancient cultures. So Propaganda Fide printed in 1910 an abbreviated Roman Ritual in Ge’ez,15 the ancient sacred language of Ethiopia, a text translated at least half a century earlier by the Vincentian bishop Saint Justin de Jacobis (†1860).

The First World War, which was so destructive for Europe in the short and long term, had a more positive effect on Cath-olic sensibilities. Hundreds of thousands of troops had come from distant outposts of the [British] Empire to fight in Europe and then return home. Some colonies acquired new rulers. The Holy See, especially under Pope Pius XI, encouraged the ordination of indigenous clergy and the expansion of missionary work.

In 1919 Benedict XV had published Maximum illud, an encyclical on missionary questions; it was followed in 1920 by an instruction of Propaganda Fide to missionaries, Qui institutum, which spelled out two significant language rights the faithful enjoyed in missionary territories: the right to have religious instruction and private prayers in their own language; but also the right to go to confession in their own language, without having to learn the language of their missionary confessors.16 Simple to say, but this commenced a vast program for change in its day and one which affected attitudes to language in the celebration of the sacraments. It was also an age when transport and communications were becoming ever easier, literacy was on the increase, and awareness of the missions was being vigorously promoted in countries of European language and culture.

The Popular Translations for the People

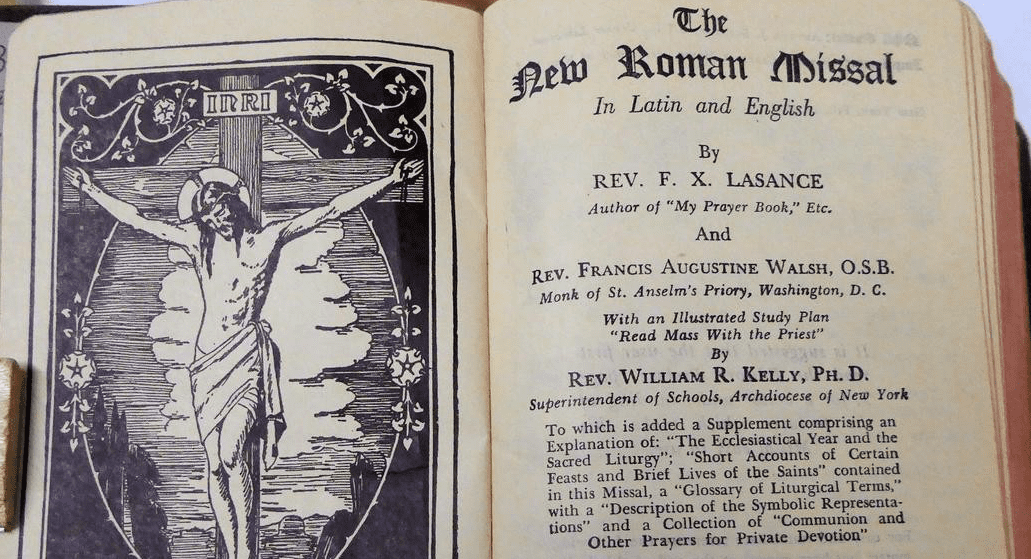

As a result of cheaper mass printing, widespread literacy, and the providential expansion of the liturgical movement, the first half of the 20th century saw a great increase in the number of hand Missals published for the people, which naturally included vernacular translations.

These were not something entirely new. They had in fact been the object of papal sanctions in the 17th century, and later when they appeared in French, mistrusted largely because of the fear of Jansenist influence. By the start of the 20th century these prohibitions were no longer in effect and the Holy See’s changed attitude was clear when the Italian publisher Marietti received congratulations from Pope Benedict XV on the publication of a bilingual Latin-Italian Missal for the faithful.17

Similar initiatives in various other European languages received similar encouragement, such as the famous German- language Missal by Dom Anselm Schott, which by 1939 had sold 1,650,000 copies.18 This trend continued after the Second World War.

These vernacular translation Missals, sometimes bilingual, were handsome people’s prayer books, modeled perhaps on the Protestant market for personal Bibles. They often contained devotional as well as liturgical texts. I remember these in my childhood as small religious status symbols, but also as sources of genuine devotion. This phenomenon was described by Pope Benedict XVI in one of his last public audiences, a meeting with the clergy of Rome. Speaking ex tempore, he mentions the prayerbooks and says that “the people prayed with their own prayer books, prepared in accordance with the heart of the people, seeking to translate the lofty content, the elevated language of classical liturgy into more emotional words, closer to the hearts of the people.”

The pope went on to explain: “But it was as if there were two parallel liturgies: the priest with the altar-servers, who celebrated Mass according to the Missal, and the laity, who prayed during Mass using their own prayer books, at the same time, while knowing substantially what was happening on the altar.” Subsequent to this came “the rediscovery of the beauty, the profundity, the historical, human, and spiritual riches of the Missal.” Then the situation had to change. The realization came, as Pope Benedict later explained, that “there should truly be a dialogue between priest and people: truly the liturgy of the altar and the liturgy of the people should form one single liturgy, an active participation, such that the riches reach the people.”19 We shall return to this later.

The Vernacular in Liturgical Books 1945-1962

Progress toward the increased use of the vernacular in liturgical books of the Roman Rite was slow, although use of the vernacular in certain rituals had been allowed for some time,20 e.g., Rome in 1935 approved a bilingual part-ritual for the use of the Austrian diocese of Vienna, allowing some use of German.21 After the war this kind of concession multiplied, for French in 1947, 1953, and 1955,22 for Hindi in India in 1949,23 for German more generally in 1950,24 for English in 1954 for the United States of America,25 and then for Canada, Australia, and other English-speaking countries.

It is important to note that these and other concessions quoted in their decree of approval a significant phrase taken from the great encyclical of Pope Pius XII, Mediator Dei, published on 20 November 1947. The phrase was this: “In non paucis ritibus vulgati sermonis usurpatio valde utilis apud populum existere potest.”26 This happens to be virtually the same phrase as that adopted by Sacrosanctum Concilium (no. 63): “the use of the vernacular tongue in the administration of the sacraments and sacramentals can often be of considerable help to the people.”27

I shall not attempt to cover all the details of the decision taken by the Council and the gradual extension of permission for vernacular translations that followed. However, it seems to me important that in the wake of commemorative events like the present one, the whole fascinating question of the vernacular and liturgical translations be researched anew and its history written impartially from the primary sources. Many of the earlier treatments were written to show what a bad thing the vernacular would be, or what a good thing it would or might be. Some portrayed the vernacular as a scurrilous move of one or other religious order, etc. It would be useful also, I feel, to revisit not just the chronicles of the day, but the underlying theological and pastoral debate.

In this connection, I should like to make one brief quotation from an article written by the well known liturgist Monsignor Aimé-Georges Martimort, in 1958, when the partial French Ritual we have mentioned was already in widespread use. Martimort writes this:

Nor must we see in the vernacular a panacea. If we were to believe some, until we get this decision, nothing can be done and when we do get it, everything will be easy. These types of pastoral escapism are one as bad as the other. Because the language problem is not the only problem, nor the first among them, because in the rites where the vernacular is allowed, such as in a baptism, it shows up the need for the priest to give catechesis and to have a profound biblical culture….28

Martimort identified rightly one major problem, when he discounted the idea that it was enough to translate the liturgy and all would be well. Translating the liturgy into the vernacular is a good thing, but not the end of the story.

Let’s now change perspective again to link more solidly the issue of language with that of the Liturgy.

The Centrality of the Liturgy

We all know that the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium calls the Liturgy “the source and summit of the entire activity of the Church” (SC 10). With this background Blessed John Paul II urged us all to rediscover a sense of “wonder” or “stupor” at the Eucharist,29 and hence by implication of the whole of the Liturgy, which is nothing more than the extension of the same sacramental principle into the realities of our earthly life in Christ.30

The Vital Importance of Faithful Liturgical Translations

If the Liturgy is such a vital matter for the Church, it is important that we understand the crucial role of liturgical language in the call to conversion and in the maintenance and enrichment of Catholic community life.

In everyday life, we can be tempted at various moments to counter what others are saying by dismissing them as “mere words.” However, in calmer moments we all know that words have great power, as do gestures and pictures and symbols. Think for a moment of the world history of the last century, the Nuremberg rallies, perverse swastikas, salutes, and political slogans. Or think of all the astuteness and persuasiveness of modern advertisements for cars, jams, smartphones, and airline companies. Fortunes are spent, because these advertisements not only change opinions, but produce huge lucrative markets.

I do not need to dwell on the obvious value of the well-known axiom Lex credendi legem statuat supplicandi and its history.31 The Magisterium in modern times has often emphasized the connections between prayer and belief.

Recently I came across a phrase uttered long before the Council by Pope Pius XI (audience of 12 December 1935), who defined the Liturgy as “the most important organ of the Ordinary Magisterium of the Church.”32 Words do not just talk. Rather, words teach, communicate, engage, persuade, counsel, console, save. What the liturgy conveys in matters of faith goes far beyond dogma; it brings about that action of the Church which, as the Constitution on Divine Revelation Dei Verbum says (no. 8), sees her perpetuating and transmitting “to every generation all that she herself is, all that she believes.”33

Pius XI did not speak lightly. As a scholar, he had dedicated his energies to long research and reflection on the renewal of the Ambrosian Liturgy and as pope he had laid the foundations for the long-term careful renewal of the Roman Liturgy by founding in 1930 a new scholarly section within the Congregation of Rites. He knew better than most what care for the text of the Liturgy meant.

The liturgy is full of technical terms. A vast number come to us from the pages of the Scriptures. While they have a meaning we can certainly call “technical,” they also often have a meaning that comes from the contexts in which the Scriptures use them. The terms “meek and humble,” which come to us from the lips of Jesus Himself (Mt 11:29), have by that fact an immense power to touch the heart. We remember the Lord’s declaration: “The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life” (Jn 6:63 RSV), just as we remember that the Letter to the Hebrews tells us “the word of God is living and active … discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb 4:12 RSV).

Apart from the massive presence in the liturgical books of Scripture readings and chants taken from the Bible, it is hardly surprising that the words of Scripture are the web and weft, the very texture and substance of the liturgical prayers that the Church herself has composed down the long centuries. Pope Paul VI reminded us of this simply but powerfully when he spoke of the Bible as the basic prayerbook of the modern Christian and affirmed, “What is needed is that texts of prayers and chants should draw their inspiration and their wording from the Bible.”34 Here the pope was only echoing a point in the teaching of the Second Vatican Council (SC 24), which reads:

Sacred Scripture is of the greatest importance in the celebration of the liturgy. For it is from Scripture that lessons are read and explained in the homily, and psalms are sung; the prayers, collects, and liturgical songs are scriptural in their inspiration and their force, and it is from the Scriptures that actions and signs derive their meaning.35

In fact, in order to grasp something of this bond between the Scriptures and the liturgy, it can be instructive to take a page of the Church Fathers or of the medieval monastic authors such as Saint Bernard. Many editions mark by special typeface the quotations and allusions to the Scriptures in these texts, but even the rest of the page is often little more than a mosaic of biblical terms or a paraphrase of biblical ideas. In a preacher like Saint Bernard, his thoughts come from the Bible, and his speech comes from the Bible. He has an intimate knowledge of the Bible to the point that we can say he exemplifies the fulfillment of Saint Paul’s exhortation in introducing the famous Philippians hymn, where he says: “Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus…” (Phil 2:5 Douay-Rheims). Saint Bernard has the mind of Christ, thinks the thoughts of Christ, and speaks the words of Christ, because he is simply steeped in the Scriptures.

In one way or another the words and ideas in the prayers can be traced back to the Scriptures, and the awareness of this has to grow in the Church of the future.

Admittedly, not all liturgical terms are biblical strictly speaking. I mention here two such categories. One of these consists of the terms that are derived, like much of our cultural heritage, from the Greco-Roman world. They have a technical sense connected with the act of sacrifice, or of offering tribute, or of addressing with due respect the divinity. They help support the structure of our traditional prayers, they are the beams and struts of our house, important in the collects of the Roman rite, but they are not its substance.

Closer again to the very essentials of our liturgical prayer are terms like “homoousion,” which in Latin became “consubstantialem,” a term hammered out with great difficulty by the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea of 325 ad, to safeguard a truth upon which our salvation depends, namely the divinity of Christ Our Lord.

Looking back over some of our remarks so far, we see how Martimort was right in his prognosis: to introduce vernacular translations into liturgical use “a profound biblical culture” is needed36 or its absence will become all too evident and damaging. Pope Pius XI was certainly right in saying (and he said it, by the way, to the great liturgist Abbot Bernard Capelle) that the Liturgy is “the most important organ of the Ordinary Magisterium of the Church.”37 How could it be otherwise, if its substance is biblical through and through?

And remember what Pope Benedict said in such a kindly way about the prayerbooks of his childhood, that they sought “to translate the lofty content, the elevated language of classical liturgy into more emotional words, closer to the hearts of the people” before it became evident that this was not enough, and that it was imperative that the people, too, have access to “the beauty, the profundity, the historical, human, and spiritual riches of the Missal.”38

But [Jesus] answered, “It is written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.’” (Mt 4:4 RSV-CE).

The New “Latin”

Before moving on, I should like to place again on the record a point that is far from original, but has enormous practical consequences. With the displacement of Latin as the usual language of worship, its central place has been taken especially by Spanish and English, while Portuguese, French, and German remain important. All this is widely recognized. The relative importance of these languages continues to shift, but Spanish can lay claim to be the formal, top-level language or at least “lingua franca” of practically half the Cath-olics throughout the world, while English is the predominant language for economics, trade, and much of advertising. It is also used for international political dialogue and often serves as the de facto base language for liturgical translations in Asia and parts of Africa. Without doubt Mandarin Chinese and Hindi will become increasingly important in this “Asian century” of Catholic missionary expansion.

II. TWO INSTRUCTIONS (AND A FEW OTHER DOCUMENTS)

The Instruction Comme le prévoit

The provisions of the Liturgy Constitution on the use of vernacular liturgical translations produced excitement and high expectations. What did this decision really mean? Where would it lead? Who would do the translations? What would they be like?

The Consilium set up by Pope Paul VI to implement the Liturgy Constitution soon began to tackle some of these points. Although the energies of the Holy See were largely occupied in reformulating the Latin books, a circular letter of Cardinal Lercaro, President of the Consilium, in October 1964 already spelled out the Council’s hint (SC 36, 3) that at least in each major language, there should be a single translation of the Liturgy.39

A month or so before the Council’s closure, a convention for translators was held in Rome in 1965, at which papers were read by bishops and experts. Pope Paul VI, a regular scrutinizer of the signs of the times, addressed the participants with a speech pointing to the responsibility of liturgical translators and saying famously that translations were becoming “the voice of the Church.” He also urged that while the language should be readily comprehensible, it should also “be worthy of the heavenly realities it signifies, different from the habits of everyday speech used in the streets and public places, such that it touches the mind and inflames hearts with the love of God.”40

With an eye to continuity, we see in these apparently simple remarks of Pope Paul an echo of Pius XI’s defining the Liturgy as “the most important organ of the Ordinary Magisterium of the Church,”41 but also of the Patriarch Theodore Balsamon’s insisting on “exact versions of the customary prayers,” and the Holy Office’s requirement about translations not into “vulgar but the erudite” language.42

Various other points concerning translations were eventually fixed by the Consilium, but looking back to those years it is evident that as the liturgical changes gradually eventuated, so the question of proper translations came to the fore. Provisional norms for translation of the Roman Canon were sent out to the bishops in 1967,43 and a few months later for the Graduale Simplex.44 But there were others, and it soon became evident that a set of more coordinated norms would be necessary.

A group appointed to draft these norms began work in April 1967, and the Ninth General Assembly of the Consilium in October 1968 approved a draft set of such liturgical norms, which were then sent to Pope Paul for his consideration. They were intended as a working document without the force of law and they were drawn up in French, which in those times was generally regarded as the second language of cultured Italians and also as the second language of the Roman Curia. It is said that the pope, who spoke elegant French, received a somewhat mediocre Italian translation to examine. In any case, he replied just before New Year 1969 to the effect that in general the norms were approved, but that he found them a bit long. By the end of the month they were published in French, with the title “Instruction” (apparently at Pope Paul’s wish). However, despite the title, the status accorded them continued to be somewhat low, and Comme le prévoit, as it was called, remained only as a document of the Consilium. In fact, the document never appeared in Latin nor was it published in the pages of the Acta Apostolicae Sedis, the official gazette of the Holy See.

There is insufficient time for a detailed analysis of different sections here. I would, however, like to point out rapidly some of the features.

The document first sets out general principles (nos. 5-29), then treats particular cases (nos. 30-37), and concludes by discussing procedures for organization of the work (nos. 38-42). It is perspicacious in distinguishing the various genres of text, and requiring a specific translation approach for each (no. 26). It is strict in insisting on a translation of the essential sacramental formulas that is integral and faithful, without variation, omission, or additions (no. 33). It maintains the principle of a single translation in each language (no. 41).

We find also in Comme le prévoit wise reminders about some of the pitfalls of translation work, such as the fact that the meaning of a single term evolves over the centuries, and the trap of ignoring how cognates in different languages have changed significance (the so-called faux-amis). It also warns of the difference between recognition by the eye of printed words on the page and spoken words captured by the ear (quite a big issue in English and French, for example).

Much of the content is entirely commendable, since in fact the document did succeed in gathering together much of the common experience of liturgical translators to that date. It aimed in large part at avoiding the imposition of a style of translation that would be more like that of the old hand-Missals of the faithful, and it made a plea for a dignified style and for traditional religious language, pointing also to the dangers of relying on schoolboy Latin and emphasizing the importance of letting biblical ideas emerge.

The Instruction’s weaknesses echo in some degree the lapidary character of the provisions of Sacrosanctum Concilium. In a document like the Constitution this pithiness is deliberate. The art is to say enough, but not too much, leaving room for prudent application in ways not foreseeable at the point of departure. When these norms are put into practice, these issues are still present, but the balance is now different. This said, Comme le prévoit was a little naive, striving perhaps to be all things to all men. More fatally, it spoke — if briefly — of “adaptations” to be effected by translations (no. 34).

What of the aftermath?

I am not sufficiently conversant with what happened in the other major European language groups to comment, but I can note features of the international English-language context into which Comme le prévoit entered and for which we can hardly impute responsibility to its redactors. It is clear to me, however, that it provided enough footholds for those who had been attracted and impressed by the very concrete example of Good News for Modern Man.

What was Good News for Modern Man, I hear you ask.

Some of you may remember it. It was a translation of the New Testament that came out in 1966. I am told that in about five years, it sold some 30 million copies. They later finished the Old Testament and renamed the full Bible the Good News Bible: The Bible in Today’s English Version, and then later still the Good News Translation. It is still published. This was a sincere attempt to get across the saving message of Our Lord to people, in a Protestant perspective; leaving aside what the translators considered “formal” language. It is not the only translation of its kind, even in English. The idea in part was to provide Christians from Asia and Africa with a Bible text in English that was easier for them to understand, and it incidentally seemed to fit the bill for young people in the West whose contact with traditional Christian communities was declining. A simple text that hits home by the freshness of the message of Jesus: that was the ambition and the millions of sales attest to its influence.

The underlying philosophy, as I have stated it, clearly owes a lot to a Protestant viewpoint, and the idea that you can get rid of the middleman, especially the Church, the priesthood, and put a Christian believer in direct touch with God. A Catholic viewpoint would obviously see the Church as having an important role in transmitting not just the Bible text, but the Word of God understood as embracing also Tradition, and mediating grace in Christ by means of the sacraments. After all, the Lord Himself left us no writings. The New Testament writings were produced under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, by Christian disciples, from within the Christian communities. Later on, in a long process, it was the Church who established the canon of Scriptures that defined and so limited the corpus of inspired books, rejecting a large number of apocryphal gospels, epistles, acts.

We need also to bear in mind that English is a language that has itself been shaped in many particulars precisely by the contents of the Bible and that any attempt to jettison these very same elements is deeply misguided.

I do not wish to spend much more time this morning on this particular translation, the Good News Bible, which even now is on the one hand widely praised and on the other fiercely contested by some Protestants on and off the internet, even described as “wicked.” On a linguistic front it owes something to projects such as the “Basic English” proposed by Charles Kay Ogden in 1930, artificially simplified English, which had for example, only 18 verbs.

While this Bible translation — or extended paraphrase — had no formal links with the Catholic Church, it provided a popular cultural context for the interpretation of Comme le prévoit. Moreover, the English translation of Comme le prévoit that circulated was virtually a rewrite, and the result was an even looser set of guidelines than the French original. In practice, it was seen as boiling down to a simple rule, “dynamic equivalence,” where unfortunately the translation was not always equivalent and even less frequently dynamic. This was a sort of shorthand for a translation approach propagated by the American Protestant academic and pastor Eugene Nida [1914-2011], a major figure in the American Bible Society. This school of thought used the expression “dynamic equivalence” (sometimes called “functional equivalence” or more recently “thought-for-thought”) to describe a certain kind of freer rendering of the original. The opposite approach came to be dubbed “formal equivalence” and is sometimes called simplistically “word-for-word.”

In a talk delivered some three years ago, Bishop Arthur Serratelli, a biblical scholar of long experience and currently Chairman of the International Commission on English in the Liturgy, pointed out45 that in its very first paragraph, the Instruction Comme le prévoit foresaw that “after sufficient experiment and passage of time, all translations will need review.” This was natural enough, given the newness and vastness of the enterprise, along with the pressure under which work was being done.

So, there we have it, Comme le prévoit. A document of somewhat uncertain status, of a provisional character, a pioneer in the way it pointed to some of the tasks and pitfalls, but based on limited experience and in the end incomplete, somewhat misleading and unsatisfactory in its results.

And yet, the goal was a lofty one. In the same parting conversation with the clergy of Rome last year, Pope Benedict, describing the great gains of the Council, has this to say (and I quote):

Then there were the principles: intelligibility, instead of being locked up in an unknown language that is no longer spoken, and also active participation. Unfortunately, these principles have also been misunderstood. Intelligibility does not mean banality, because the great texts of the liturgy — even when, thanks be to God, they are spoken in our mother tongue — are not easily intelligible, they demand ongoing formation on the part of the Christian if he is to grow and enter ever more deeply into the mystery and so arrive at understanding. And also the word of God — when I think of the daily sequence of Old Testament readings, and of the Pauline Epistles, the Gospels: who could say that he understands immediately, simply because the language is his own? Only ongoing formation of hearts and minds can truly create intelligibility and participation that is something more than external activity, but rather the entry of the person, of my being, into the communion of the Church and thus into communion with Christ.46

The Instruction Liturgiam authenticam

It was practically two decades later that Blessed John Paul II — in his 1988 Apostolic Letter Vicesimus quintus annus, which he issued to mark the 25th anniversary of Sacrosanctum Concilium — remarked that the quality of the vernacular editions of the liturgical books was not satisfactory.47 We just heard Pope Benedict sum it up last year in the word “banality.” This was a perception shared in the 1980s by not a few bishops. For example, within little more than a decade after the publication of the first complete English-language translation of the Missal by the “mixed commission” known as ICEL, ICEL itself took the lead in launching a program of retranslation.48

In 1988, Pope John Paul II called for, among other things, the bishops’ conferences to live up to their responsibilities for the liturgical translations, replacing provisional translations, completing the range of books, correcting infelicities and errors, ensuring wide cooperation, all with the aim of arriving at stable liturgical books of a dignity commensurate with the mysteries of the faith which they serve to celebrate!49

On 25 January 1994, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments issued the Instruction Varietates legitimae, a document which sets out to comment on nos. 37-40 of Sacrosanctum Concilium, and thus to discuss and give guidance to the complex operation of the inculturation of the Roman Liturgy. It is a rich and subtle document, worthy of study. I mention it here simply because it in effect rejected the claim that when the new vernacular translations of the liturgical books deviated from saying what was said in the Latin, this was legitimate, for “cultural reasons.” Now Varietates legitimae treated liturgical inculturation in a sympathetic and clearheaded way, which by implication brought translators back to the sophisticated work of accurate, intelligible translation rather than liturgical engineering.

It was noticeable — and some did notice — that the Instruction Varietates legitimae makes no mention of Comme le prévoit.

Varietates legitimae also did a good job of pointing out the connections inherent in the liturgical texts between the words, deeds, and intentions of the Savior (no. 25), the biblical substratum of the liturgy (no. 23), and the basic principles found also in the great liturgical families of the East from the time of the Apostles (no. 26).

Apart from offering a variety of considerations around what is laid down in Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Instruction Varietates legitimae also speaks in a historical perspective about the process of inculturation as it relates to the application of linguistic expression, to the transition from one language to another in liturgical celebration, and to the relation between biblical texts and concepts and derivative ecclesiastical usage.

When it discusses the use of the vernacular in the liturgy, the Instruction is principally concerned with defining the type of language to be used. Here it does not deflect from the requirements we have so often seen above, this language “manifestet semper oportet, una cum fidei veritate, maiestatem ac sanctitatem mysteriorum, quae celebrantur” (no. 39). It adds a reference to the need to be wary of undesirable connotations of language in other — especially pagan — religions,50 and to the appropriateness of respecting the nature of the different literary genres (no. 39). In no. 40 the question of music and singing is raised, whereby cautions are added about the words and their quality both liturgical and literary. Finally, in no. 50 the question is raised of areas where the language situation is fragmented. Every effort should be made to strike a balance and so avoid excessive liturgical fragmentation around languages and take account of the fact that a country may be moving toward use of one single main language.

In 1997 Blessed John Paul II followed up his own Vicesimus quintus annus and the Varietates legitimae of the Congregation for Divine Worship by asking the latter to begin drafting new translation norms51 for the major languages, but also for a few hundred other languages which have been approved for introduction into full liturgical use. This decision, as we have seen, was not the opinion of a single moment, but had matured in the Church and in the thinking of the late pope over a period of time.

The Congregation had no more leisure available to it in 1997 than the Consilium had in 1967 as it was working on a much delayed new edition of the Latin text of the Roman Missal. Yet that made the moment all the more crucial, and so it became imperative to complete new guidelines on translation to accompany in some sense the new Latin Missal and to orientate the new translations that would have to follow.

In due time the new set of norms was completed and was approved by John Paul II in 2001, as Liturgiam authenticam the Fifth Instruction “for the right implementation of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council.”52 This set out new rules for organizing and carrying out liturgical translations into the vernacular. I would like to read to you one essential paragraph that will help us grasp the thrust of the whole document (I quote):

The Latin liturgical texts of the Roman Rite, while drawing on centuries of ecclesial experience in transmitting the faith of the Church received from the Fathers, are themselves the fruit of the liturgical renewal, just recently brought forth. In order that such a rich patrimony may be preserved and passed on through the centuries, it is to be kept in mind from the beginning that the translation of the liturgical texts of the Roman Liturgy is not so much a work of creative innovation as it is of rendering the original texts faithfully and accurately into the vernacular language. While it is permissible to arrange the wording, the syntax and the style in such a way as to prepare a flowing vernacular text suitable to the rhythm of popular prayer, the original text, insofar as possible, must be translated integrally and in the most exact manner, without omissions or additions in terms of its content, and without paraphrases or glosses. Any adaptation to the characteristics or the nature of the various vernacular languages is to be sober and discreet [no. 20].

There are a number of notes being sounded here and we can paraphrase some of them as follows:

1) Our patrimony of faith, in the expression that is specific to the Roman Rite down the centuries, is to be carefully kept, even in translation;

2) Translation is not a superficial business of reinventing the wheel, of making the Church say what some translator wants her to say, but the carrying across of a well-honed, well-defined, and vital content, guaranteed by high authority, into the language we speak today;

3) If we take English as the example, it is clear that the English has to be good English, but not at the cost of diminishing or distorting the precious original content.

I think I have made it clear what kind of translations of liturgical texts we need. Let us just say charitably that we haven’t always had them. Vague, imprecise, ideological, and at times quirky translations that astonishingly moved away from biblical language have for almost two generations hindered effective catechesis in some important language areas. Beautiful and ancient prayers that are a synthesis of the spiritual doctrine and teaching of the Fathers of the Church, with deep biblical roots, were lost to view, and this in the middle of an unprecedented religious crisis. How very sad.

I have been surprised to find that there is so little academic examination of Liturgiam authenticam.53 My surprise is linked in part to the fact that Liturgiam authenticam does much more than give detailed instructions on how to translate. It seeks to persuade and explain theologically the minds of Blessed John Paul II and Pope Benedict on the liturgy.

Liturgiam authenticam picked up on the pope’s remark in Vicesimus quintus annus that a satisfactory situation had not yet been reached in the matter of the quality of the vernacular translations of the liturgical books.54 In tackling this problem, the Instruction mentions repeatedly that the time for a new era for liturgical translations has come and should now begin, so that through their means an authentic liturgical renewal may come about.55

Liturgiam authenticam also makes a strong series of references to Varietates legitimae.56 It in some sense imitates Varietates legitimae by taking the form of an extended technical comment on no. 36 of Sacrosanctum Concilium, and thus providing a set of guidelines on translation, just as Varietates legitimae set out to comment on the Constitution’s nos. 37-40, and give guidelines on inculturation in relation to the liturgy.

The new document discussed five distinct questions: the choice of modern languages for admission into the liturgy; the criteria for the preparation of translations of liturgical texts; procedures to be observed in such preparation and the bodies to be entrusted with the tasks; issues regarding the publication of the liturgical books; and procedures for the translation of the liturgical Propers of dioceses and religious families.

One strong emphasis spells out the need for the bishops to take effective charge of preparing and approving liturgical translations,57 in harmony with neighboring bishops’ conferences or with those using the same language,58 and in harmony with the Holy See.59 Such an appropriate legal framework and procedures are, of course, required by Catholic ecclesiology.

The necessity of careful pastoral planning and the development of a strategy for the use of languages in the Liturgy over a given territory are also emphasized.60 Once again this is a task primarily for the bishops.

The document distinguishes between the already difficult task of translation and the notion of “adaptation.” In fact, while it is undoubtedly true that the living use of any language and certainly the passage from one language to another, imply a certain degree of “adaptation,” the translator cannot distort or develop the text in an arbitrary or ideological way. Liturgiam authenticam acknowledges (no. 20) that the liturgical books have already been revised at least once since the Council61 and that if need arises it will be done again, but that the translator is not the person to do this, nor should it be done surreptitiously. In so acting, the translator would usurp the primary role of the bishops and the prerogatives of the Holy See.

To facilitate its implementation, the document mentions the possibility of drafting (in agreement with the Holy See) a ratio translationis,62 a set of application guidelines, and perhaps a specialized dictionary or specialized word lists that spell out equivalents for key Latin terms, based especially on Bible translation work that has proved successful. As someone who has worked on material of this kind for long hours, I can report that it is not an easy option, but the end result is enlightening and an immense help in maintaining doctrinal and liturgical integrity. In some Western languages this material is in part already available. In other languages it is not and needs to be created.

Liturgiam authenticam is a rich and important document. It is a game changer. Its first fruit is the new English translation of the Roman Missal; a wonderful achievement.

Of this whole operation of reworking our liturgical translations, Blessed John Paul II, who set it in motion, said:

I urge the bishops and the Congregation to make every effort to ensure that liturgical translations are faithful to the original of the respective typical editions in the Latin language. A translation, in fact, is not an exercise in creativity, but a meticulous task of preserving the meaning of the original without changes, omissions or additions. The failure to observe this criterion on occasion makes the work of revising some texts necessary and urgent.63

The instruction acknowledged that the text must be accessible to the listener, but must not be dumbed down. The theological and linguistic richness of the original texts must be uncovered and retained. Not just concepts, but words and expressions are to be translated faithfully64 to respect the wealth contained in the original text. Some may find such exactness a bit discomfiting, but it is a price worth paying to preserve the purity of the liturgical and theological traditions embodied in the rites.

Liturgiam authenticam has ambitions which go beyond translation itself because it “envisions and seeks to prepare for a new era of liturgical renewal, which is consonant with the qualities and the traditions of the particular Churches, but which safeguards also the faith and the unity of the whole Church of God.”65 As Blessed John Paul II put it, quoting the Lord (Lk 5:4), “Duc in altum”!66 A truly great enterprise.

Along with bishops throughout the English-speaking world, I have been heavily involved in the development of the new English translation of the Missal, following the norms set out by Liturgiam authenticam. In general terms, it has been a great pastoral success and is already part of the Church landscape.

As to criticisms, I make my own a remark I heard some while ago from a fellow bishop, namely that if ever in the history of the Church there was a collegial decision affecting a single major language group, this is it. The text was prepared and then improved by virtually all the bishops sharing our common English-language, and combed through line by line, word by word, in two high-level international committees of bishops and experts meeting assiduously over the best part of a decade. It was endorsed by every bishops’ conference using the English language, in secret votes requiring a two-thirds majority.

As we are here in commemoration of the promulgation of the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium, on 3 December 1963, I should like to conclude with the help of Pope Benedict, quoting another passage of those ex tempore comments he made to the clergy of Rome at more or less this time last year. Talking of the unfolding of the Council, Pope Benedict said:

I find now, looking back, that it was a very good idea to begin with the liturgy, because in this way the primacy of God could appear, the primacy of adoration. “Operi Dei nihil praeponatur”: this phrase from the Rule of Saint Benedict (cf. 43:3) thus emerges as the supreme rule of the Council. Some have made the criticism that the Council spoke of many things, but not of God. It did speak of God! And this was the first thing that it did, that substantial speaking of God and opening up all the people, the whole of God’s holy people, to the adoration of God, in the common celebration of the liturgy of the Body and Blood of Christ. In this sense, over and above the practical factors that advised against beginning straight away with controversial topics, it was, let us say, truly an act of Providence that at the beginning of the Council was the liturgy, God, adoration.67

We have now entered the Franciscan years, a time of great hope with the first Jesuit pope, the first South American and the first pope to take the name Francis.

Just as Francis of Assisi still captures the imagination of many outside as well as inside the Church, so too Pope Francis has changed the Church’s public image through- out most of the world, ensuring a new openness for Christ’s kerygma.

Blessed John Paul II and especially Pope Benedict struggled for years to purify the Catholic liturgical traditions — especially in the Roman rite. They realized that the vitality of Catholic life is always linked to the prayerfulness, faith, and cohesion of the worshipping communities.

Proper translations are an essential part of the liturgical renewal; and the liturgical renewal of Vatican II, of Blessed John Paul, and Benedict XVI, provides an equally necessary foundation for the missionary work of Pope Francis.

This liturgical and doctrinal tradition will continue to flourish and bear fruit amid the structural changes in the Holy See and the pastoral initiatives which are likely to characterize Pope Francis’s pontificate.

Notes:

1 Cf. Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, Instruction, Varietates legitimae, of 25 January 1994, no. 17, in Acta Apostolicae Sedis 87 (1995) 288-314, here p. 294.

2 Cf. Theodor Klauser, ‘Der Übergang der römischen Kirche von der griechischen zur lateinischen Liturgiesprache’, in Miscellanea Giovanni Mercati, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano, vol. 1, 1946 (Studi e Testi 121), pp. 467-482; Christine Mohrmann, ‘Les origines de la latinité chrétienne à Rome’, in Vigiliae christianae 3 (1949) 67-106, 163-183.

3 Cf. Cyrille Vogel, Medieval Liturgy: An Introduction to the Sources, Pastoral Press, Washington DC, 1986 (= NPM Studies in Church Music and Liturgy s.n.), p. 297.

4 Egeria, Itinerarium, cap. 47, in Ezio Franceschini & Robert Weber, “Itinerarium Egeriae”, in Paul Geyer (et alii), Itineraria et alia geographica, Brepols, Turnholti, 1965 (Corpus christianorum, series latina 175), pp. 28-90, here pp. 88-89.

5 Mario Righetti, Manuale di Storia Liturgica, Ancora, Milano, vol. III, 3a edizione, 1966 (reprint 1998), pp. 272-274; Pietro Borella, “La lingua volgare nella liturgia”, in Ambrosius 44 (1968) 71-94, 137-168, 237-266, here pp. 74-75, 79-82.

6 Heinrich Vehlen, “Geschichtliches zur Übersetzung des Missale Romanum”, in Liturgisches Leben 3 (1936) 89-97, here pp. 89-90; Josef Andreas Jungmann, Missarum sollemnia: Eine genetische Erklärung der römischen Messe, Herder, Wien, 3. Auflage, 1962, Band I, p. 190.

7 N. Kowalsky, “Römische Entscheidungen über den Gebrauch der Landessprache bei der heiligen Messe”, in Neue Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft 9 (1953) 241-251, here p. 241; Cyrille Korolevskij, Liturgie en langue vivante: Orient et Occident, Cerf, Paris, 1955 (C. Lex orandi 18), p. 136.

8 Cf. C. Korolevskij, Liturgie en langue vivante, pp. 138-141.

10 Interrogationes canonicae sanctissimi Patriarchae Alexandriae, Domini Marci, et Responsiones ad eas sanctissimi Patriarchae Antiochiae, Domini Theodori Balsamonis, Resp. ad inter. 5, in PG 138: 957; cf. C. Korolevskij, Liturgie en langue vivante, pp. 30-31.

11 Cherubino Segvic, “Le origini del rito slavo-latino in Dalmazia e Croazia”, in Ephemerides Liturgicae 54 (1940) 38-65; C. Korolevskij, Liturgie en langue vivante, pp. 130, 132-133.

12 Texts in François Bontinck, La lutte autour de la liturgie chinoise aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Nauwelaerts, Louvain, 1962 (Publications de l’Université Lovanium de Léopoldville 11), pp. 409-411, 411-412.

13 Texts such as the Missale Chaldaicum of 1767 or the Missale Syriacum of 1843.

14 Ronald Pilkington, “La liturgia nel Sinodo Ricciano di Pistoia”, in Ephemerides Liturgicae 43 (1929) 410-424, here pp. 413-414; P. Borella, “La lingua volgare nella liturgia”, pp. 243-246; Owen Chadwick, The Popes and European Revolution, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 418-431, 628; cf. Pius VI, Constitutio, Auctorem fidei, of 28 August 1794, esp. n. 66: in Heinrich Denzinger & Adolf Schönmetzer (edd.), Enchiridion Symbolorum definitionum et declarationum de rebus fidei et morum, Herder, Friburgi Brisgoviae, editio XXXVI emendata 1976, nn. 2600-2700, esp. n. 2666.

15 Cf. C. Korolevskij, Liturgie en langue vivante, p. 203.

16 Documenta ad instaurationem liturgicam spectantia, CLV-Edizioni Liturgiche, Roma, 2002, nn. 1071-1074, pp. 279-280.

17 Questions liturgiques et paroissiales 7 (1922) 3-4.

18 H. Vehlen, “Geschichtliches”, p. 96; J.A. Jungmann, Missarum sollemnia, Band I, p. 214.

19 Pope Benedict XVI, Address to the Parish Priests and the Clergy of Rome, 14 February 2013: in Acta Apostolicae Sedis 105 (2013) 283-294, here pp. 286-287.