Online Edition:

November 2013

Vol. XIX, No. 8

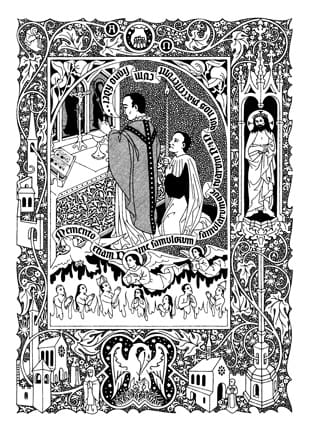

Memento Mori: Remembrance of the Dead

©

Daniel Mitsui 2013

by Daniel Mitsui

This is the second in a series of articles in which I explain my attempts to draw upon the riches of traditional Catholic art in my own contemporary work.

This ink drawing was commissioned as a design for a Mass intention card, specifically for Masses offered for the dead. My patron wanted it to communicate the application of the graces of the Mass to the souls in purgatory.

I drew a priest celebrating Mass, at the moment when the faithful departed are remembered. The prayer that he is beginning to read is known as the Diptychs of the Dead, because in the early Church, the names of those commemorated were written on a literal diptych, a pair of folding tablets of wood or ivory:

Memento etiam, Domine, famulorum, famularumque tuarum N. et N. qui nos praecesserunt cum signo fidei et dormiunt in somno pacis. Ipsis, Domine, et omnibus in Christo quiescentibus, locum refrigerii, lucis et pacis, ut indulgeas, deprecamur. Per eumdem Christum Dominum nostrum. Amen.

Remember also, Lord, your servants N. and N., who have gone before us with the sign of faith and rest in the sleep of peace. Grant them, O Lord, we pray, and all who sleep in Christ, a place of refreshment, light and peace. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.1

I wrote the beginning of the Latin text on a banderole, a pictorial device that represents spoken words in medieval art. These long, twisting scrolls serve a function similar to that of speech balloons in comic strips and comic books.

The scene of the Mass shows a common medieval liturgical practice. The server holds an elevation torch, a blessed candle that was held by deacons, subdeacons, and other ministers during the consecration and elevation of the Sacred Host, and that burned until the priest’s communion. The faithful departed of the late Middle Ages often would bequeath the six candles burned around their coffins for this purpose.2

This reflects the belief that a candle symbolically represents the prayers of someone who otherwise cannot be present. Votive candles representing the intentions of a particular person were sometimes made with a wick equal in length to that person’s height; the candle was then doubled over and twisted around itself to attain a more manageable size.3

In the lower part of the drawing, the Holy Spirit carries the priest’s prayer to a company of suffering souls in purgatory. Angels follow, pouring a cooling laver over them. I borrowed this image from an illuminated manuscript of a 15th-century Middle English prose translation of Guillaume de Deguileville’s Pilgrimage of the Soul, a visionary journey through hell, purgatory, and heaven.4

The decorative border was inspired by the borders in a Missal illuminated in 14th-century England for Sherborne Abbey, and in the printed Books of Hours produced by the partnership of Philippe Pigouchet and Simon Vostre in 15th-century France. The border includes mages of church buildings, clergymen, hermits, and a Gothic monstrance holding the Man of Sorrows, surrounded by decorative vines, flowers, and criblé (tiny white dots).

At the top, I drew an emblem of the Hand of God the Father holding five tiny figures representing the souls of the righteous. This traditional symbol5 refers to the words of Psalm 138 (Thy right hand shall hold me) and the Book of Wisdom (The souls of the just are in the Hand of God).

In a quatrefoil in the bas-de-page, I drew a pelican in her piety, a type of Jesus Christ. Medieval legend explains that the self-sacrificial pelican feeds her young with her own blood.

This same symbol is found in the text of Saint Thomas Aquinas’s eucharistic hymn Adoro Te Devote:

Pie Pelicane, Jesu Domine,

Me immundum munda tuo sanguine:

Cujus una stilla salvum facere

Totum mundum quit ab omni scelere.

O loving Pelican! O Jesu, Lord!

Unclean I am, but cleanse me in Thy Blood;

Of which a single drop, for sinners spilt,

Is ransom for a world’s entire guilt.6

The symbolic association of the pelican with the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ and of His Precious Blood made it, to my mind, especially appropriate to accompany an image of a Mass offered for the dead.

Notes

1 English translation of The Roman Missal. International Committee on English in the Liturgy, 2010 (old.usccb.org/romanmissal/order-of-mass. pdf).

2 Eamon Duffy. The Stripping of the Altars. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005, pp. 96-97.

4 New York Public Library, Spencer ms. 019, ff. 48-49.

5 F.R. Weber. Church Symbolism. Cleveland: J.H. Jansen, 1938, p. 50.

***

Daniel Mitsui, editorial consultant to The Adoremus Bulletin, specializes in ink drawings, and is currently working to establish Millefleur Press for publishing fine printed books. One of his most prestigious projects was his illustration of a new edition of the Roman Pontifical, commissioned by the Vatican in 2011. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Michelle, a classical singer, and their three children. His work can be seen online at danielmitsui.com.

****

***

*