Online Edition:

September 2013

Vol. XIX, No. 6

Sacred Art: The Imprint of God through Time

Style and Symbol Transcends Culture, History

©

Daniel Mitsui

by Daniel Mitsui

The contemporary religious artist faces a peculiar challenge; his culture provides no single vigorous artistic tradition to guide his hand. He rather has access to a superabundance of art historical information. With but a little research, he can view reproductions of the art of nearly every century and every nation. This is the first in a series of articles explaining my own attempts to make sense of this vast inheritance and to draw upon it for my own work.

In the 15th century, the Dominican Alanus de Rupe vigorously promoted devotion to the Holy Rosary in his preaching. He authored Unser Lieben Frauen Psalter (Psalter of Our Blessed Lady), a devotional book explaining the proper method for praying the Rosary. The posthumous edition that was published by Konrad Dickmut in 1483 contains illustrations in which each set of five mysteries is grouped together on a single page.

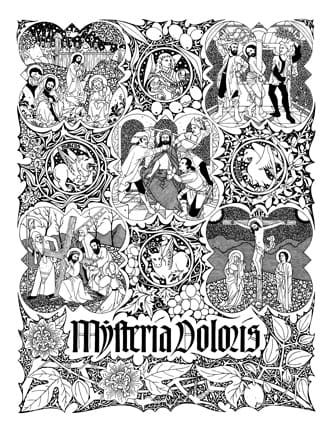

In tribute to this and similar works, I drew my own picture of the Sorrowful Mysteries in a black and white style resembling a relief print in an early printed book; I used Northern European paintings and prints from the same era as models for the five scenes. These include the Grey Passion — a series of panel paintings by Hans Holbein the Elder, and the monochrome picture of Christ carrying His cross on the outer wing of Hieronymus Bosch’s famous Temptation of Saint Anthony triptych. Both of these were painted around 1500.

What impressed me most when researching these artistic models was that even at the very end of the Middle Ages, a time of enormous technological, social, and philosophical change, the religious artists remained faithful to inherited traditions. In the works by Rogier van der Weyden (c 1400-1464), Gerard David (c 1460- 1523), and Martin Schongauer (c 1448-1491) that inspired the Crucifixion scene here, the content and arrangement is essentially the same as that found in Mozarabic illuminated manuscripts, Roman frescoes, and Byzantine icons made centuries earlier: Mary stands at Christ’s right hand and rests her head on her hands; Saint John stands barefoot on the other side, holding a book. (Here, the book is somewhat concealed in the folds of his garment.) A skull at the base of the Cross indicates Calvary (Golgotha in Aramaic), the place of the skull; according to an old tradition, the skull of Adam was buried in this spot by Shem, the son of Noah.

These artists seem to have been convinced that every detail of a traditional composition bears witness to a continuously perpetuated memory of the sacred event depicted, or contains an important theological message. It is this conviction that I hope to maintain in my own religious art.

The ornament surrounding the five quatrefoils is composed of plants related to Christ’s Passion: olives (for the Garden of Gethsemane), hyssop, myrrh-bearing tree, grapevine, and jujube (which is widely supposed to have supplied the branches out of which the Crown of Thorns was woven). There is also a symbol of more recent origin toward the bottom of the page; a passion vine, whose flower has parts that resemble the Crown of Thorns, the Holy Nails, and the Five Wounds. One of the jujube thorns pricks a passion fruit, from which a drop of red juice falls, suggesting the blood that flowed from Christ’s side.

The symbolism of plants and animals is to my mind one of the most important aspects of the Catholic artistic tradition, for it inculcates a habit of seeing the imprint of God in Nature. In my mind, this worldview, as much as reverence for tradition, distinguishes truly religious art.

***

Daniel Mitsui, editorial consultant to The Adoremus Bulletin, is an artist who specializes in ink drawings. He attended Dartmouth College from 2000 to 2004, where he studied drawing, painting, printmaking, and film animation. He is currently working to establish Millefleur Press, an imprint for publishing fine printed books. One of his most prestigious projects was completed in 2011, when the Vatican commissioned him to illustrate a new edition of the Roman Pontifical. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Michelle, a classical singer, and their two sons. His work can be seen online at danielmitsui.com.

***

*