Online Edition:

December 2012

Vol. XVIII, No. 9

Music, Poetry, Liturgy — and Their Silences

by Donald DeMarco

When Mozart remarked that in music the silences are more important than the sounds, he was saying something both provocative as well as profound. How can silences, seemingly moments of musical emptiness, have any importance? The great pianist Artur Schnabel was once asked how he managed to become a pre-eminent interpreter of Beethoven. His answer was, in its own way, a confirmation of Mozart’s remark: “The notes I handle no better than many pianists. But the pauses between the notes — ah, that is where the art resides.”

Music is composed of sound and silence, just as reality consists of matter and spirit, the finite and the infinite. Music is our most spiritual art because its silences are best suited to permit the entrance of another world. The notes set up the silences, not unlike the way a door frame circumscribes a passageway. And just as the passageway is more important than the door frame, silences — a pathway to the spiritual — can be more important than the sounds.

A single example from the world of music illustrates the point. Consider the extended silence in Handel’s Messiah before the final “Hallelujah” in the “Hallelujah Chorus.” The music builds to the point where nothing more can be stated in sound. At that apex, sound defers to silence, and the spiritual impact on the listener is felt, dramatically and emphatically.

On the level of poetry, Percy Bysshe Shelley has referred to the poet’s art as “arresting the vanishing apparitions which haunt the interlunations of life.” The rarely used word “interlunations” warrants some explanation. In a literal sense, it means, “between two full moons” (inter + luna). Figuratively, it refers to the spaces or moments of silence that separate one life event from another. It is precisely through these interlunations, or openings, that a transcendent message can break through.

“Vanishing apparitions,” though felt, are not subject to empirical confirmation. They are real, but spiritual and evanescent. They have their decided impact, although they cannot be reiterated or rediscovered at will. One may be reminded here of William Wordsworth’s lament that for him, “there hath past away a glory from the earth”:There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparelled in celestial

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

Our materialist world is intent on crowding out silence, and therefore, opportunities to glimpse, however fleeting, a sense of the transcendent. There are popular forms of music in which the amplification of sound and frenetic rhythms assure that it conveys nothing of the spiritual. The same avoidance of spiritual interlunations is implied in such popular phrases that capture the tempo of modern life as “time is money,” “continuous entertainment,” “non- stop flights,” “fabulous fun-filled weekend,” “never a dull moment,” “we are open 25 hours a day, 8 days a week,” and so on.

The material dimension, itself, cannot convey either the spiritual or the infinite. One cannot squeeze the infinite out of the finite. Music, poetry, and the Liturgy offer us wonderful opportunities to be freed from material containment, and to sense another and more resplendent world. We suffocate, spiritually, when we are enclosed in the material order.

Martin Buber had a strong sense of how the tandem of music and poetry could liberate us from the confines of the material order and bring to our awareness a sense of the supernatural. In his celebrated work I and Thou, he makes the following statement:

There are moments of silent depth in which you look on the world-order fully present. Then in its very flight the note will be heard; but the ordered world is its indistinguishable score. These moments are immortal, and most transitory of all; no content may be secured from them, but their power invades creation and the knowledge of man…

Buber’s distinction between the “ordered-world” and the “world-order” is of particular significance. The “ordered-world” is a rational conception. It is the creation of mathematicians and materialists. It is logical but not allusive, systematic but not symbolic. It is spiritually stifling. The “world-order” is the way the world truly is, consisting of the rational existing in close proximity with the trans-rational. It is a world of depth, one that can speak to us from beyond. It is a world that allows the Creator to speak to us through His creation.

Buber alludes to a parallel distinction to the one between an “ordered-world” and the “world-order,” namely one that occurs between the music score and music. Clearly, music is more than the music score. The relationship between the latter and the former is equivalent to that between a blueprint and life, prescription and art, mathematics and mysticism. There are performers who stick so closely to the music score that they do not breathe life into the music. But what exactly is the difference between a mechanical performance and one that is truly artistic? It is impossible to describe in words, though musicians can readily discern its reality. So, too, one can sense the presence of the spiritual within the interlunations of life as well as through the silences in music.

The Italian/Swiss poet Arturo Fornaro has exquisitely integrated music and poetry to illustrate the spiritual significance of silence in his poem Il Silenzio:

Dio,

Ho cercato

Su tutti gli strumenti

La nota piú alta

Che arrivasse fino a Te.

Ho toccata

Il silenzio,

E Tu mi has risposto.

(God,/I have sought in vain/Upon every instrument/For that highest note/Whose sound would reach You./But when I touched the silence,/Then You answered me.)

Liturgy, in order to transmit a sense of God and a sense of the sacred more effectively, has two great allies at its disposal: music and poetry. It is important, however, to mention that these two fine arts are at their best in this regard, when they allow the transcendent to be transmitted through their respective silences. Mozart was right, and works of his such as Ave Verum, to cite but a single example, are marvelously suited to the essential aim of the Liturgy.

***

Donald DeMarco, professor emeritus at St. Jerome’s University, Waterloo, Ontario, and adjunct professor at Holy Apostles College and Seminary, Cromwell, Connecticut, is a senior fellow of Human Life International. Dr. DeMarco’s most recent article in AB, “Tuning to the Right Frequency,” appeared in September 2012.

***

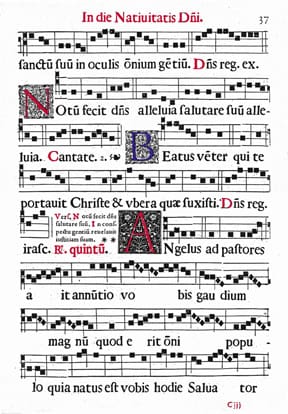

Illustration: In die Nativitatis Domini (On the Day of the Nativity of the Lord), page from a 17th c. French antiphonary. (Private collection). The Latin words say, in part, “The Angel said to the shepherds, ‘Great joy to you and to all people, for unto you is born this day a Savior…’”

***

*