Online Edition:

November 2008

Vol. XIV, No. 8

In Search of Lost Symbols in Scripture

On Comtemporary Biblical Illiteracy

by Monsignor Timothy Verdon

Editor’s Note:

Monsignor Timothy Verdon served as a peritus (expert) at the Synod of Bishops on the Word of God held at the Vatican in October. He is a Yale-trained art historian and has lived in Italy since the 1960s. He became a priest of the Archdiocese of Florence in 1995 and currently directs the diocesan office for catechesis through art. Monsignor Verdon, who is a canon of the Florence Cathedral and member of the board of directors of the Cathedral Museum, has served as Consultant to the Vatican Commission for the Artistic Heritage of the Church and teaches for Stanford University’s study program in Florence. A former fellow of the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Villa I Tatti, Florence, he is the author of numerous articles and books, in Italian and English, on religious art, including Mary in Western Art, and The Churches of Florence.

Monsignor Verdon’s article that appears here was published Sunday, October 12, 2008, in L’Osservatore Romano, and in the online journal www.chiesa, edited by Sandro Magister, and is reprinted in AB with permission.

While the Synod of Bishops meditates on the word of God in the life and mission of the Church, it might be useful to reflect on what could be called “contemporary Biblical illiteracy”, meaning the almost total loss of the instincts and techniques that over the centuries have shaped the Christian manner of approaching the sacred page.

In order to realize the gravity of the situation, it is enough to consider the illustrated manuscripts produced in the medieval monasteries for liturgical use.

The modern observer who comes into contact with such treasures in the context of an exhibition or a book on art history may not even understand the distance that separates us today from the world that shaped these: there are, in fact, such basic differences between our “bookish” experience and that of the Middle Ages that we risk not even noticing them. In the age of the internet, the concept of “book” already begins to escape us, and in the light of modern biblical and liturgical studies, the traditional idea of a “sacred book” has a meaning that is similarly different from the one it had in the past. In practice, it is almost impossible today to conceive the sacred authority that a biblical or liturgical text had in the Middle Ages.

This same thing is true of the miniatures that adorn the text. Our age, saturated with brilliantly colored images in magazines, in newspapers, on television — instant photos, live feeds, computer- generated images — is unable to grasp the surprise, the delicious freshness of these clear-hued miniatures, glittering with gold among the compact columns of writing in a manuscript. Nor are we able to restore the intellectual and emotional relationship between the given image and an ancient text, known, loved, believed.

And yet for more than a thousand years of European history, the typical context of books was precisely that of a faith that was intensely lived, profoundly meditated upon, and nourished by texts so ancient that they seemed “eternal”: texts that placed the reader on the border between his own situation and universal realities, the liminal context that we can define simply with the term “prayer”. Liturgical books serve, in fact, for community prayer, and the Bible for “lectio divina”[sacred reading], which in its turn was nourished and in a certain way shaped by the liturgy and by devotion.

By the liturgy, we mean the entire complex of ecclesiastical rites, with — at the center — the Eucharistic liturgy or Mass. The texts of the Mass, which vary according to the feasts or periods of the year, effectively require a sort of community “lectio divina”, a docility in the interpretation of the event or person celebrated, which we must call contemplative. Everything is continually brought back to the mystical center of the Christian faith, the sacrifice that Christ accomplished by dying on the cross, and to the new life of His resurrection. Even on Christmas Eve, the readings at Mass require connecting the joy of birth with the dramatic fact of death on the cross; the infant body in the manger, the crucified body of the adult man, the “Corpus Christi” really present in the Eucharistic bread and the “Mystical Body” constituted by the community gathered in prayer become one and the same thing. This is why the fresco in the basilica of Assisi, depicting Saint Francis placing the Child in the manger of the crèche in Greccio, is situated beneath a large cross and next to the altar.

This is a way of seeing — and understanding — the causal relations among historical, meta-historical, and supernatural events, a way different from our own: this manner of seeing — and understanding — influenced the manner in which the contents of the text were read, imagined, and depicted.

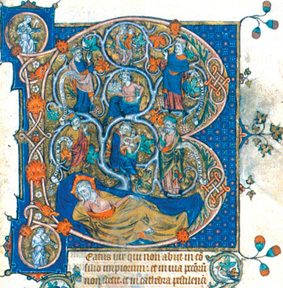

Let’s take the example of the a splendid initial painted in the 14th-century breviary in the Queriniana city library in Brescia; it is the “B” of the first word of Psalm 1, in the Latin Vulgate: Beatus vir qui non abiit in consilio impiorum, blessed is the man who has not walked in the counsel of the wicked.

The fathers of the Church interpreted the beginning of the psalm as referring to Christ, so the miniaturist who painted the “B” used the open spaces to evoke the entire life of Christ, with scenes of the annunciation, the nativity, the crucifixion and burial. By placing the words Beatus vir in the initial and on the edge beneath these scenes, the anonymous artist is associating the “beatitude” of the human relationship with God — the theme of the psalm — with Jesus Christ.

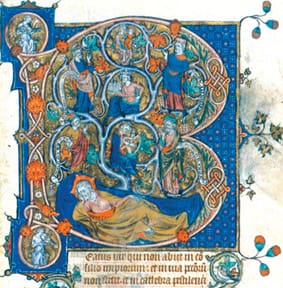

[Editor’s note: The reader will notice the illustration on this page is not the same as the one Monsignor Verdon describes; however, it is a similar contemporary initial for the same Psalm. Instead of the Life of Christ, the artist who illuminated this early 14th-century English Psalter depicted the “Tree of Jesse”, which shows the lineage of the Messiah in Hebrew Scriptures. The family tree, allegorically mentioned in Psalm 1, is “rooted” in the sleeping figure of Jesse, whose son David appears above him crowned and holding a harp. On the branch above them is David’s son, Solomon, who holds a model of his Temple. This image of the Jesse Tree is surmounted with the Infant Christ in the arms of His mother, Mary. The figures are flanked by the Old Testament Prophets, Jeremiah and Hosea on the left, Isaiah and Zachariah on the right.]

The ancient way of reading also had an allegorical dimension that, in the modern age of scientific Biblical studies, we risk losing.

The antiphon of the Benedictus for Lauds for the solemnity of the Epiphany, for example, connects in an extraordinarily evocative way the three biblical events that, in their chronological sequence, together constitute the first manifestation of Christ to the world: the arrival of the Magi bringing gifts to the newborn Jesus (Matthew 2:1-12); the baptism of the thirty-year-old Jesus in the Jordan River (Matthew 3:13-17; Mark 1:9-11; Luke 3:21-22); and the changing of water into wine at the wedding in Cana (John 2:1-12). But the anonymous author of the antiphon inverts the chronological order, and puts the wedding before the baptism, saying: “Today the heavenly bridegroom unites Himself to His Church, which Christ washes from sin in the Jordan”.

Having evoked in this way the marriage of God with His people, promised by the prophets, in addition to the obligation of the “bridegroom” to purify his “bride” by washing her (cf. Ephesians 5:25-27), the author then introduces the Magi, bringing them with their gifts as guests invited to the wedding feast, the diners at which are finally made joyful by the water changed into wine at Christ’s first miracle, in Cana: “Hodie caelesti Sponso juncta est Ecclesia, quoniam in Iordane lavit eius crimina: currunt cum munere Magi ad regales nuptias, et ex acqua facto vino laetantur conviviae, alleluia!” Translated, it says: “Today the heavenly Bridegroom is joined with His Church, because He has washed her sins in the Jordan. The Magi come with gifts to the royal wedding, and the banqueters rejoice in the water changed into wine. Alleluia!”

The first and last words of the antiphon explain this style of reading: “hodie” and “Alleluia!” Here the texts of the New Testament are interpreted in the light of the liturgy, and in the liturgy the sense of time changes, so that past events, even those that took place sequentially, are experienced ecstatically in the one “today” of God, with the effect of transforming impossible historical overlaps into co-present and interpenetrating mysteries. Every event sheds light on every other event, in the one plan of the Father revealed by the life-death-resurrection of Christ: this is the “forma mentis” [form, idea, mental approach] underlying countless Christian images, from the catacombs to the twenty-first century.

Both the illustrated initial and the antiphon for Epiphany are the results of monastic imagination, and this origin is of fundamental importance. Monasticism is itself a work of art: it makes visible and tangible a particular intensity of Christian life, because the monk wants to be, like Christ, the icon or image of the beauty of God; and the monastery is that place in which, with the help of their brethren who share the same interior vision, work can be perfected in tranquility, in a sort of laboratory of the soul.

The most widespread form of monastic life in the West, the Regula monachorum [monastic rule] of Saint Benedict of Norcia, explicitly invokes this analogy when it compares the monastery to the shop of a craftsman, characterizing the entire life of the monks as a creative process (Regula 4, 75-78). This affirmation echoes a more ancient tradition, which imagined the life of every believer as adorned “with the gold of good works and with the mosaics of persevering faith”.

What makes the monks different from other Christians, at least in the thought of Saint Benedict, is the extent of their commitment: the monks employed the entirety of their human energies in spiritual projects, having for “tools” the moral precepts of Christian life, “instrumenta artis spiritalis” [instruments of spiritual art] (Regula 4, 75).

Although the meaning of these statements is clearly metaphorical, it is not surprising that the metaphor was turned into reality, and that the monasteries became powerhouses for the arts, as Saint Benedict himself anticipated (cf. Chapter 57 of the rule, on “Craftsmen in the monastery”).

A climate of creativity in one sector of experience prompts similar creativity in other sectors, and moreover the monastic life fosters the production of sacred art because, with the exclusion of profane distractions, it permits the artist to immerse himself in the Scriptures and in the sacramental actions that give color and form to his faith, furthermore guaranteeing him a devoted and prepared “public”.

In the history of Christianity, the cultural fruits of monasticism have not been limited to the monks, because the silence and withdrawn life of the monasteries, instead of keeping away the mass of the faithful, has attracted them, and monastic history confirms the fascination that monks have always raised in large segments of society.

Long before Alcuin taught or Anselm wrote, the citizens of Alexandria in Egypt went into the desert to listen to the abbot Saint Anthony, and the Romans brought their children to Saint Benedict. Even when the golden age of monastic culture began to fade, beginning in the 13th and 14th century, the ideal of a solitude filled with prayer would remain the paradigm for the active religious orders of the late Middle Ages, and for the laity to whom they preached.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the formal achievements of the monks — their art and architecture, their liturgical and devotional practices, their organizational structures and methods of education, agriculture, and trade — shaped the cultural awareness of Europe. Even more, monastic life itself, considered a creative and free decision, was deeply imprinted in the imagination of Christians, to the point that some of the most fundamental aspirations of our civilization can be interpreted only in the light of the monastic “enterprise”.

In all of this, it is important to grasp the twofold role of the imagination. On the one hand, monastic life requires an effort of the imagination in those who embrace it by becoming monks; on the other, it requires an effort of imagination in those who do not become monks, in Christian society in general. The man or woman who gives up the legitimate goods of life, withdrawing in order to seek God in silence and prayer, needs a significant capacity of social and moral imagination in order to persevere in believing in “what eye has not seen, and ear has not heard, but God has prepared for those who love Him” (I Corinthians 2:9): this passage is, in fact, cited in the rule of Saint Benedict (4:77). Above all in the sometimes problematic relationship with his confreres, in addition to the faith it is also the imagination that permits the monk to feel that “whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me” (Matthew 25:40; cf. Regula 36:3).

By a similar act of imagination, those who do not enter the monastery have chosen, over centuries, to consider the monks “wise men” and “prophets” rather than dangerous dissidents at the margin of society. From the thousands of people who went to the abbot Anthony in the Egyptian desert, seeking a word, to the hundreds of thousands who today read Thomas Merton, Christians have believed that the solitude of the monks does not imply disdain for others, and that from their silence can emerge a wisdom at the service of man.

Moving in its simplicity, this trust suggests the most important function of monasticism in the imaginative life of Christians, that of a “symbol” that transmits sanctity to those who approach it. The visitors to a monastery, like the monks themselves, have the impression that, in the contemplative recollection of the cloister, places and things take on something of the intentionality and dedication of the inhabitants of those places.

The objects, even the humble ones, suddenly are perceived as signs that reveal the solidarity between man and the sacred, steps on the ladder reaching from earth to heaven. Precisely in this spirit, Saint Benedict says that even the ordinary implements of the monastery must be treated as if they were sacred vessels for the liturgy (Regula 31:10).

This is a sacramental way of seeing, in which the surface of things becomes transparent in order to reveal an infinite perspective, granting power to images.

A depiction of the Last Supper in a monastic refectory, like the one by Leonardo da Vinci at Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, is not only a decoration, but also a functional object that communicates and nourishes the faith from which it emerges.

The practical choices in the formal genesis of the work, which normally are part of the history of art, are interwoven here with other choices, not aesthetic, but existential.

***

*