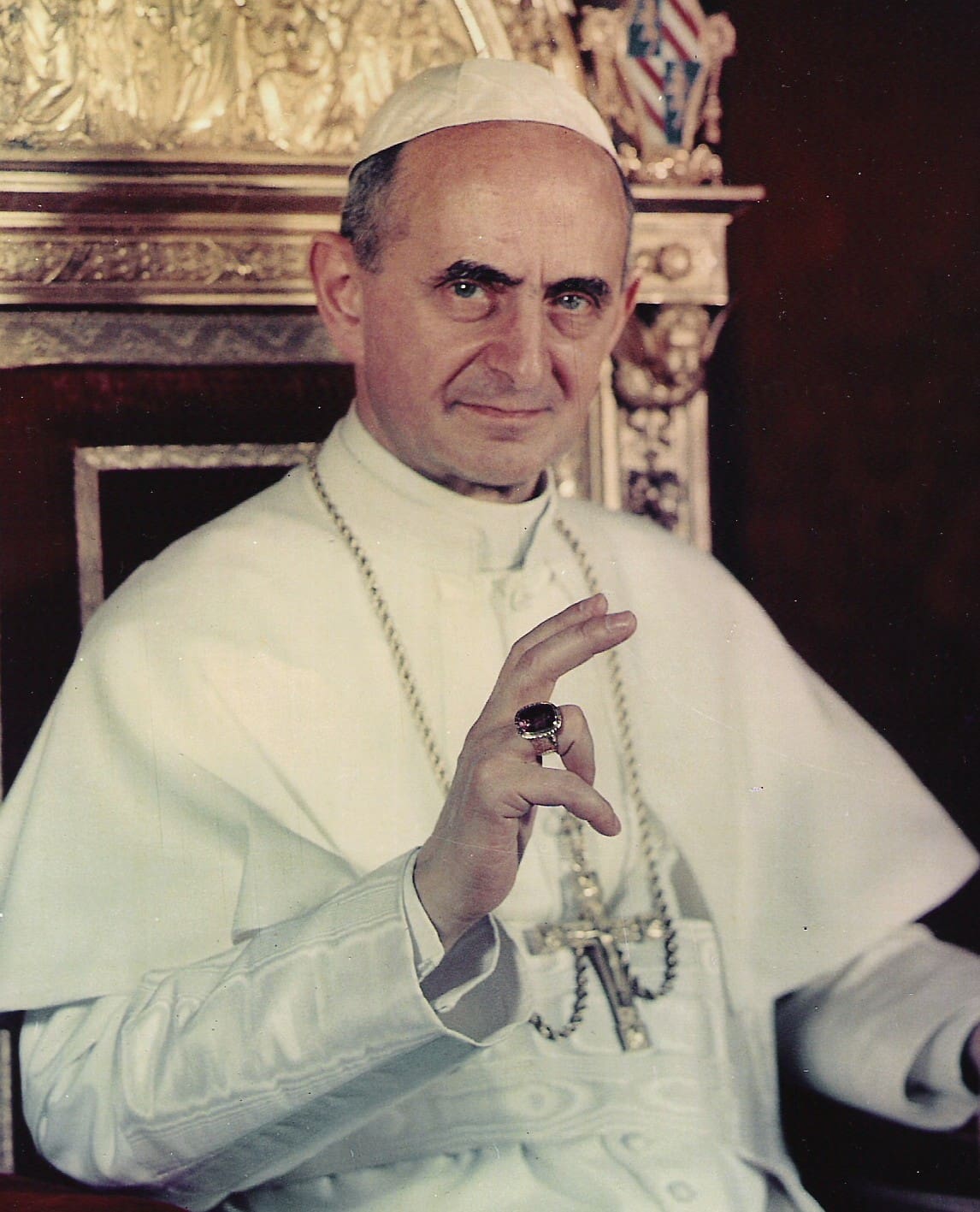

Apostolic Constitution

Issued by His Holiness Pope Paul VI

The Roman Missal, promulgated in 1570 by Our predecessor, St. Pius V, by decree of the Council of Trent,1 has been received by all as one of the numerous and admirable fruits which the holy Council has spread throughout the entire Church of Christ. For four centuries, not only has it furnished the priests of the Latin Rite with the norms for the celebration of the Eucharistic Sacrifice, but also the saintly heralds of the Gospel have carried it almost to the entire world. Furthermore, innumerable holy men have abundantly nourished their piety towards God by its readings from Sacred Scripture or by its prayers, whose general arrangement goes back, in essence, to St. Gregory the Great.

Since that time there has grown and spread among the Christian people the liturgical renewal which, according to Pius XII, Our predecessor of venerable memory, seems to show the signs of God’s providence in the present time, a salvific action of the Holy Spirit in His Church.2 This renewal has also shown clearly that the formulas of the Roman Missal ought to be revised and enriched. The beginning of this renewal was the work of Our predecessor, this same Pius XII, in the restoration of the Paschal Vigil and of the Holy Week Rite,3 which formed the first stage of updating the Roman Missal for the present-day mentality.

The recent Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, in promulgating the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium, established the basis for the general revision of the Roman Missal: in declaring “both texts and rites should be drawn up so that they express more clearly the holy things which they signify”;4 in ordering that “the rite of the Mass is to be revised in such a way that the intrinsic nature and purpose of its several parts, as also the connection between them, can be more clearly manifested, and that devout and active participation by the faithful can be more easily accomplished”;5 in prescribing that “the treasures of the Bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God’s Word”;6 in ordering, finally, that “a new rite for concelebration is to be drawn up and incorporated into the Pontifical and into the Roman Missal.”7

One ought not to think, however, that this revision of the Roman Missal has been improvident. The progress that the liturgical sciences has accomplished in the last four centuries has, without a doubt, prepared the way. After the Council of Trent, the study “of ancient manuscripts of the Vatican library and of others gathered elsewhere,” as Our predecessor, St. Pius V, indicates in the Apostolic Constitution Quo primum, has greatly helped for the revision of the Roman Missal. Since then, however, more ancient liturgical sources have been discovered and published and at the same time liturgical formulas of the Oriental Church have become better known. Many wish that the riches, both doctrinal and spiritual, might not be hidden in the darkness of the libraries, but on the contrary might be brought into the light to illumine and nourish the spirits and souls of Christians.

Let us show now, in broad lines, the new composition of the Roman Missal. First of all, in a General Instruction, which serves as a preface for the book, the new regulations are set forth for the celebration of the Eucharistic Sacrifice, concerning the rites and the functions of each of the participants and sacred furnishings and places.

The major innovation concerns the Eucharistic Prayer. If in the Roman Rite, the first part of this Prayer, the Preface, has preserved diverse formulation in the course of the centuries, the second part, on the contrary, called “Canon of the Action,” took on an unchangeable form during the fourth and fifth centuries; conversely, the Eastern liturgies allowed for this variety in their anaphoras. In this matter, however, apart from the fact that the Eucharistic Prayer is enriched by a great number of Prefaces, either derived from the ancient tradition of the Roman Church or composed recently, we have decided to add three new Canons to this Prayer. In this way the different aspects of the mystery of salvation will be emphasized and they will procure richer themes for the thanksgiving. However, for pastoral reasons, and in order to facilitate concelebration, we have ordered that the words of the Lord ought to be identical in each formulary of the Canon. Thus, in each Eucharistic Prayer, we wish that the words be pronounced thus: over the bread: ACCIPITE ET MANDUCATE EX HOC OMNES: HOC EST ENIM CORPUS MEUM, QUOD PRO VOBIS TRADETUR; over the chalice: ACCIPITE ET BIBITE EX EO OMNES: HIC EST ENIM CALIX SANGUINIS MEI NOVI ET AETERNI TESTAMENTI, QUI PRO VOBIS ET PRO MULTIS EFFUNDETUR IN REMISSIONEM PECCATORUM. HOC FACITE IN MEAM COMMEMORATIONEM. The words MYSTERIUM FIDEI, taken from the context of the words of Christ the Lord, and said by the priest, serve as an introduction to the acclamation of the faithful.

Concerning the rite of the Mass, “the rites are to be simplified, while due care is taken to preserve their substance.”8 Also to be eliminated are “elements which, with the passage of time, came to be duplicated, or were added with but little advantage,”9 above all in the rites of offering the bread and wine, and in those of the breaking of the bread and of communion.

Also, “other elements which have suffered injury through accidents of history are now to be restored to the earlier norm of the Holy Fathers”10: for example the homily,11 the “common prayer” or “prayer of the faithful,”12 the penitential rite or act of reconciliation with God and with the brothers, at the beginning of the Mass, where its proper emphasis is restored.

According to the prescription of the Second Vatican Council which prescribes that “a more representative portion of the Holy Scriptures will be read to the people over a set cycle of years,”13 and of the readings for Sunday are divided into a cycle of three years. In addition, for Sunday and feasts, the readings of the Epistle and Gospel are preceded by a reading from the Old Testament or, during Paschaltide, from the Acts of the Apostles. In this way the dynamism of the mystery of salvation, shown by the text of divine revelation, is more clearly accentuated. These widely selected biblical readings, which give to the faithful on feast days the most important part of Sacred Scripture, is completed by access to the other parts of the Holy Books read on other days.

All this is wisely ordered in such a way that there is developed more and more among the faithful a “hunger for the Word of God,”14 which, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, leads the people of the New Covenant to the perfect unity of the Church. We are fully confident that both priests and faithful will prepare their hearts more devoutly and together at the Lord’s Supper, meditating more profoundly on Sacred Scripture, and at the same time they will nourish themselves more day by day with the words of the Lord. It will follow then that according to the wishes of the Second Vatican Council, Sacred Scripture will be at the same time a perpetual source of spiritual life, an instrument of prime value for transmitting Christian doctrine and finally the center of all theology.

In this revision of the Roman Missal, in addition to the three changes mentioned above, namely, the Eucharistic Prayer, the Rite for the Mass and the Biblical Reading, other parts also have been reviewed and considerably modified: the Proper of Seasons, the Proper of Saints, the Common of Saints, ritual Masses and votive Masses. In all of these changes, particular care has been taken with the prayers: not only has their number been increased, so that the new texts might better correspond to new needs, but also their text has been restored on the testimony of the most ancient evidences. For each ferial of the principal liturgical seasons, Advent, Christmas, Lent and Easter, a proper prayer has been provided.

Even though the text of the Roman Gradual, at least that which concerns the singing, has not been changed, still, for a better understanding, the responsorial psalm, which St. Augustine and St. Leo the Great often mention, has been restored, and the Introit and Communion antiphons have been adapted for read Masses.

In conclusion, we wish to give the force of law to all that we have set forth concerning the new Roman Missal. In promulgating the official edition of the Roman Missal, Our predecessor, St. Pius V, presented it as an instrument of liturgical unity and as a witness to the purity of the worship the Church. While leaving room in the new Missal, according to the order of the Second Vatican Council, “for legitimate variations and adaptations,”15 we hope nevertheless that the Missal will be received by the faithful as an instrument which bears witness to and which affirms the common unity of all. Thus, in the great diversity of languages, one unique prayer will rise as an acceptable offering to our Father in heaven, through our High-Priest Jesus Christ, in the Holy Spirit.

We order that the prescriptions of this Constitution go into effect November 30th of this year, the first Sunday of Advent.

We wish that these Our decrees and prescriptions may be firm and effective now and in the future, notwithstanding, to the extent necessary, the apostolic constitutions and ordinances issued by Our predecessors, and other prescriptions, even those deserving particular mention and derogation.

Given at Rome, at Saint Peter’s, Holy Thursday, April 3 1969, the sixth year of Our pontificate.

PAUL VI, POPE

Footnotes

- Cf. Apost. Const. Quo primum, July 13, 1570.

- Cf. Pius XII, Discourse to the participants of the First International Congress of Pastoral Liturgy at Assisi, May 22, 1956: A.A.S. 48 (1956) 112.

- Cf. Sacred Congregation of Rites, Decree Dominicae Resurrectionis, February 9, 1951: A.A.S. 43 (1951) 128ff.; Decree Maxima Redemptionis nostrae mysteria, November 16, 1955: A.A.S. 47 (1955) 838ff.

- Vatican Council, Const. on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, art. 21: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 106.

- Ibid., art. 50: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 114.

- Ibid., art. 51: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 114.

- Ibid., art. 58: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 115.

- Ibid., art. 50: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 114.

- Ibid.

- Cf. Ibid.

- Cf. Ibid., art. 52: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 114.

- Cf. Ibid., art. 53: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 114.

- Ibid., art. 51: A.A.S. 56 (1964) 114.

- Cf. Amos 8:11.

- II Vatican Council, Const. on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Consilium, art. 38: A.A.S. 56 (1964).