Online Edition –

Vol. VI, No. 6-7: September/October 2000

About Making Music

Achieving "noble simplicity" in Church music is not always so simple

by Allen Brings

"He who sings prays twice", says the old adage. It is a capsule commentary on the importance of sacred music in worship; it implies the profound effect of sung music on memory, and for that reason on what one believes. The past three decades have seen the sung prayer of traditional Catholic liturgical music virtually vanish and much of today’s hymnody justly criticized as unimaginative, unmemorable and unsingable.

Allen Brings’s essay shows that, as in all forms of art, the creation of what appears to be most compellingly simple (hence memorable) requires knowledge, skill, patience and time.

Editor

There is no lack of outstanding hymns suitable to the Roman liturgy; some, like Adoro te (especially in its plainchant setting) or Praetorius’s polyphonic setting of "Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen" (It is a rose a-blooming), are masterpieces comparable to those found in any genre.

It is more difficult to compose music that is simple enough for congregations to learn, to be able to sing together, and not to tire of singing over a lifetime, although the greatest composers have done it. But though simplicity is a hallmark of hymns, it does not imply either simplemindedness or a lack of richness in telling detail.

Simplicity entails, first of all, a clarity of phrase structure in which the beginnings and ends that is, the cadences of phrases are clearly articulated by the rise and fall of the melodic line. Both the proximate and the remote relationships of all pitches must be perceptible. In addition, the forward motion of the melodic line should not be impeded by the "padding" of changes of direction or trivial ornamentation. It goes without saying that dissonant skips should never be used, but that even wide skips like sixths and octaves should be used with care.

Simplicity also demands an unvarying tactus or beat, usually based on a tempo of approximately one unit of measure per second. Although establishing a metrical pattern may be helpful, it is not essential. Sustaining pitches, that is, tying notes, from measure to measure should always be avoided, as should sustaining them longer than a measure at a time or, worst of all, pausing between phrase units while the congregation guesses when it must begin the next phrase, listening meanwhile to what is, in effect, an instrumental interlude. If the rhythm has established a duple subdivision of the beat or pulse (two eighth-notes per beat, for example), a triple or other subdivision should never be introduced.

Ranges should be singable

Beyond the re-quirement of simplicity, the pitch range of a hymn should never exceed the ranges within which most congregants can sing, whether the women are sopranos or altos or the men basses, baritones, or (least likely) tenors. Reaching for a high pitch at a melodic climax is a reasonable expectation; remaining at either end of the tessitura is taxing, especially in a hymn in which four or more verses will be sung, and should always be avoided.

What those accompanying hymns seldom recognize, too, is that four-part settings of hymns are always published at pitch levels (or in keys) that best suit choirs of mixed voices. Most hymns, when they are sung only by a congregation, need to be transposed usually a step lower to accommodate the men, who cannot indeed will not the highest pitches and will therefore most likely not sing at all, leaving the singing mostly to the sopranos, who will probably be in the majority.

However much the rendition of a hymn may be enhanced by an accompaniment, a well-designed hymn should never require it, either to help the congregation maintain its pitch level or to stay together. If the melody, furthermore, has been polyphonically conceived, the broader harmonic implications, though not the details, should be apparent even in the absence of accompaniment. The inescapable conclusion is that a hymn tune should be self-sufficient as we know plainsong has always been, whether or not it has been dressed with even the most discrete nineteenth-century harmonies.

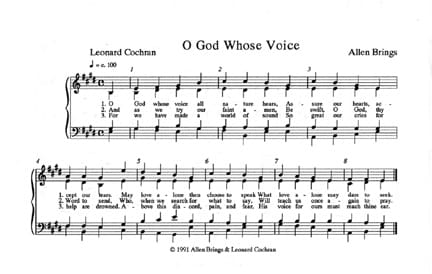

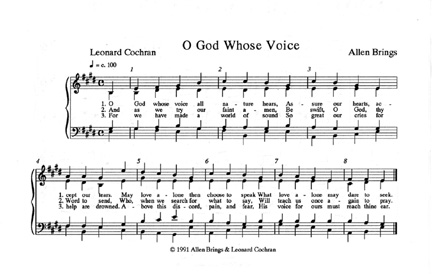

That the hymn shown illustrates what I’ve just said will, I hope, be apparent. Not so apparent may be those pitch relationships that make the tune itself memorable, (that is, easy to learn and to recall), coherent in phrase structure, yet varied enough to sustain interest during the singing of three verses or for its use over a long period of time.

To agree with the iambic meter of the text, each measure of music is t / t t, and each phrase, in order to correspond to each line of poetry, is two measures long, so that the entire hymn consists of four symmetrical phrases. Each cadence is marked by a descending step (from C# to B in the first phrase, A to G# in the second, and so on).

The framework of the tune is provided by arpeggiating (or "horizontalizing") the basic chordal sonority of the key of E major, the triad containing the pitch-classes E-G#-B (each of which is prolonged by a neighbor tone or a passing tone).

Note, for example, the presence of the tones of the triad within the first two phrases, the passing tone between E and G# in bar 1, the upper neighbor tone C# that prolongs the B in both bars 2 and 3, and the upper neighbor tone A that prolongs the G# in bar 4. Details such as the repeated note motif that concludes each phrase serve to unify the melody, especially when in bars 2 and 6 it is presented in the same form while at the very end it is presented descending from F# to E, thus forcing closure on the piece. The path taken by the highest pitch, E in bar 4, enables one to hear the four phrases in groups of two and two: from bar 1 to 4 the high C# moves slowly by step through B and A only to G#; the descent from the high E then is gradually by step through the entire scale to the end.

Tonal materials

All of these features are made possible by the decision to use the materials of the tonal, (that is, the major-minor), system of keys, materials well-known to all whether consciously or not. Because of the extreme simplicity of this tune, it resembles both a litany, with its rarely varied formula, and the psalm tone, in which there is a formulaic rise to a recitation tone a fifth above the keynote and a corresponding formulaic descent to the finalis. As in litanies and psalm tones, the focus of attention is principally on the text, where it belongs. Because of the melody’s resemblance to plainsong, congregants would probably not be surprised to see it printed in their hymnals and, by recognizing the similarity of all the rhythms even if they could not actually "read" the music would know in advance that there is no rhythmic notation for them to decipher.

The four-part setting reveals harmonic and contrapuntal details scarcely suggested by the folk plainness of the hymn tune itself. It is these details that sustain the purely musical interest of the piece and distinguish it from similar four-part settings of older repertories. While the principles are like those that have been employed for more than 300 years and are therefore familiar to congregants, who might otherwise resist something too new, their applications in this example differ in subtle ways. No one acquainted with the music of the past would confuse it with the work of Bach, Mendelssohn or Brahms.

Outer vocal lines carry tune

Because they are prevented by the presence of voices both above and below them from moving with the freedom normally exercised by the outer voices (the soprano and bass), the inner voices (alto and tenor) typically move as if they merely filled in the texture. Indeed, in all similar textures found in older repertories, roughly 85% of the harmonic information contained in a piece is conveyed by the soprano and bass lines, so that a small choir might even perform such a hymn by singing only the outer lines. Within this limited range, however, the alto and tenor lines must still move with a clear sense of direction and be able to submit to the kind of analysis already given the hymn tune, which, of course, is found in the soprano.

Modest though they may seem, these are the lines within which appear the dissonances that lend special interest to the hymn when it is heard in its complete four-part setting. A few illustrations should suffice to convey what is pervasive even in a piece as short as this.

1. On beat 1 of bar 2, the alto contains an unprepared dissonant neighbor tone while at the same time the tenor and soprano lines are preparing for simultaneous prepared dissonances (properly called suspensions) on beat 2.

2. A short "chain" of overlapping suspensions begins with beat 4 in the alto of bar 3, completing, or resolving, itself at beat 3 in the soprano.

3. Of special interest is the almost monotone B in the tenor found in the last phrase. By being consonant, that is, harmonically stable, from beat 4 of bar 6, it causes both outer voices to become descending passing-tone dissonances on beat 2 of bar 7. The B itself then becomes a prepared dissonance (a suspension, that is) on beat 1 of bar 8, but does not resolve properly because, although it moves down by step as it ought to, the resulting pitch, A, is also dissonant a practice that would have been frowned upon in earlier times but which has long been sanctioned in the twentieth century. Many of the individual chords that are the result of the confluence of the four lines display qualities that a twentieth-century composer or listener might find especially attractive, qualities that are caused by the presence and relative spacing of certain intervals.

Other observations concerning spacing and harmonic doublings could also be cited as devices that encourage a continuing interest in listening to as well as singing the four-part setting of the hymn, but there is another aspect which I would prefer to mention because of how it reflects more recent harmonic practices.

Renaissance refreshed

One of the more important stylistic trends of the twentieth century has been the refreshening of diatonicism, with its predominantly-whole-step-with-only-two-half-step scales, by adopting traits more closely associated with music of the high Renaissance than with that of eighteenth-century Classicism.

These traits can be observed in a greater incidence of secondary triads; progressions of triads whose roots are adjacent in the scale; and progressions in which the roots of triads move down a fourth rather than a fifth.

Such traits strike many as being new, even a little exotic, when, in fact, they were suggested by the music of such Renaissance masters as Josquin, Palestrina, Victoria and Orlandus Lassus. Examples may be readily found in this hymn, which lend it a more contemporary sound while still allowing it to seem traditional, especially in the phrase from beat 4 in bar 4 through to the end of that phrase on the third beat of bar 6. If this phrase had not already been preceded by two cadences that securely established the tonality of E, this third phrase would not sound truly in the key of E.

It is significant for the coherence of the music that these devices did not appear in such a concentration earlier in the hymn and that the structural, if not artistic, purpose of the fourth and last phrase is to reconfirm the prevailing tonality of the music at least by the appearance of the final cadence.

Concerning the text: I was fortunate indeed to find a poet of achievement in Leonard Cochran, a priest at the Benedictine Priory at Providence College who teaches in the English Department. Nor am I surprised that good poets like Father Cochran have musically sensitive ears.

Two of the most important musical qualities of his text are the preponderance of voiced consonants and the scarcity of unvoiced. When unvoiced consonants do occur, they come more than likely at the end of a phrase or are followed by vowels, as in line 2, when the eight syllables cantand in good choral singing should be sung thus: "A-shu-rour-hear-tsa-cce-ptour-tears". Father Cochran’s keen ear and sensitivity to sung language makes such a text graceful to both singer and composer.

The details I have cited are among those minutiae which must be considered by a serious composer, and ought to be evaluated by those who determine how a composition will be used. I shall be amply rewarded if this article positively influences the depth at which liturgical music will be discussed in the future.

Allen Brings is Professor of Music at the Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College of the City University of New York, and a director of the Weston Music Center and School of the Performing Arts in Weston, Connecticut. His article on the "Art of Lectoring" appeared in the November 2002 AB.

***

*