Online Edition

April – May 2004 — Vol. X No. 2-3

Church Architecture and "Full and Active Participation"

Does the architectural style of our churches influence the way we worship?

Chapel of Nôtre Dame-du-Haut

Copyright © 2004

by Thomas Gordon Smith

"In the restoration and development of the Sacred Liturgy the full and active participation by all the people is the paramount concern, for it is the primary, indeed the indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit".

Sacrosanctum Concilium II.141

TWO GROUPS of architects currently advocate distinct approaches to what Catholic churches should look like around 2001 AD. The dominant players are reviving the ideas and appearance of mid-twentieth century modernism. They borrow heavily from the modernist tradition of aesthetic and spatial abstraction and believe, with their clients, that their new Roman Catholic buildings help the Church move "forward" in the artistic and social senses.

A principal tenet of the modernist revival maintains the mid-twentieth century belief that we have surpassed architectural languages, such as classicism, in use before 1920. A smaller group of architects contradict such prohibition of cultural richness and diversity. They have taught themselves to practice aspects of traditional Western architecture in form, method, and meaning. They work to apply this understanding by building new churches that integrate with the continuum of traditional Catholic structures. They are not interested in the rhetoric of "moving forward" but seek to revive architectural idioms that can serve the traditional goals of finding wholeness and stasis.

French Paradigm for Neo-Modernist Catholic Churches

The key building to be aware of in analyzing the neo-modernist churches is the post-World War II chapel of Nôtre Dame-du-Haut, designed by Le Corbusier at Ronchamp in southeastern France.

During the 1920s, Le Corbusier rejected traditional architectural paradigms and substituted the idea that machines designed by engineers should become the valid models for buildings. His aphorism that "a house is a machine for living" was reflected in the platonic geometries of his seminal residences, such as the Villa Savoye of 1928-31.2 After the Second World War, Le Corbusier softened the geometrical severity of these icons. With the chapel at Ronchamp he introduced the curvilinear, syncopated, and monumental structures that marked his last two decades. Designed and built between 1950 and 1955, Nôtre Dame-du-Haut became instantly famous. It continues to signal a turning point in every textbook on the history of Western architecture.3

From the exterior, Ronchamp’s curved, prow-like walls seem to thrust from the hillside under billowing, sail-like concrete roofs (see illustration). The arris or peak of the prow is split by a vertical slit of glass and concrete mullions (glass dividers). To the right, an outdoor pulpit thrusts outward.

The left wall, built of rubble salvaged from a church shattered during the war, is perforated by scores of deeply set windows that alternately contract and expand inward. The glass is painted in the color and style of Corbusier’s version of the paintings of Matisse and Jean Miró, as is the enameled painting on the Church’s entrance door.4 A tower with a cowl-like dome rises above the door, perforated by an asymmetrical arrangement of windows and supporting a cross.

The cast-in-place concrete roof features swelling curves and contrasts with the white rough-cast stucco walls. On the interior, the walls, also covered with stucco, press inward, and the floor slopes toward the altar platform. The gray concrete ceiling drapes downward. In contrast to the exterior view, the interior volume does not expand like a wind-filled sail but contracts as though responding to a vacuum.

Completed a decade before the Second Vatican Council, Nôtre Dame-du-Haut influenced the architectural consequences of the 1960s and 70s interpretations of the liturgical documents. Architects and liturgical designers created interiors that had no spatial differentiation between narthex, nave, and sanctuary. Like Ronchamp, they disposed the pews asymmetrically. Ronchamp’s cave-like spatial dynamic, relieved by luminous points of light, was, and remains for many, a spiritually moving "liturgical space". People’s sense of the sacred at Nôtre Dame-du-Haut is often expressed in vague terms because the building’s aesthetic is emotive and expressionistic.

Le Corbusier was manifestly not interested in hierarchical functional and volumetric differentiation any more than he approved of traditional iconic imagery or classical architectural vocabulary. He and the generation he influenced were motivated to create churches that looked entirely new by relying on prevailing theories of expressionism in art.

When judged by the influence Ronchamp had on architects of the 1950s and 60s who designed Catholic churches, Le Corbusier’s model at Ronchamp was wildly successful. In the United States alone, hundreds of substantial churches of many denominations follow its lead and thousands of meditation chapels in American hospitals echo the interior of Nôtre Dame-du-Haut.

Influence Persists for Half a Century

As Catholics anticipated the millennium during the 1990s, some church leaders developed commissions for new institutions and churches. The more prominent projects have resulted in a distinct revival of the aesthetic and ideology behind Le Corbusier’s Nôtre Dame-du-Haut. The initial design for the Pope John Paul II Cultural Center in Washington, DC was based on nostalgic and naïve quotations from Ronchamp. These were updated and made more sophisticated in the actual building, but the allusions are still clear.

A church in the newly gentrified south-Loop district of Chicago, Old St. Mary’s, is a reinterpretation Nôtre Dame-du-Haut in the single volume of its "Liturgical Space", the expressionistic stained glass throughout, and the angled focus toward the altar. The baptismal pool at St. Mary’s even traces the shape of Ronchamp in microcosm.

The most significant architectural example is the cathedral church of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles, California. The interior of this monument exploits many variations on the central themes of Ronchamp (see illustration on facing page).

One enters the cathedral indirectly with a corridor ceiling supported at points on the wall like Nôtre Dame-du-Haut. At the back of the church, the floor slopes toward an undifferentiated sanctuary surrounded by asymmetrical arrangements of pews. Like Ronchamp, the ceiling presses down in descending curvatures and the walls are pierced with deep embrasures that filter light.

The project for Our Lady of the Angels was developed and presented — beginning in the mid-1990s — with an extremely sophisticated public relations strategy. The elite of the Los Angeles cultural establishment were to be involved in developing and orienting the artistic aspects of the project.

Initially, deconstructionist architects were considered, but a more conservative choice was made in awarding the job to Spanish architect José Rafael Moneo. Promoters of the cathedral plans overcame the outcry criticizing the building’s cost as well as the controversial imagery created by Los Angeles artists and sculptors.

The exterior of Our Lady of the Angels has a chunky cubism that resembles Ronchamp in spirit but not in form. The interior, however, is clearly dependent on the fifty-year-old French model. Nonetheless, the cathedral is officially promoted as being new, different, and forward looking.

The popular press reinforced this view when responding to the dedication of Our Lady of the Angels in late August 2002. The author of an article in Time magazine asserted that the cathedral is "a sign that the cleansing operation of modern architecture has been embraced for one of the most ambitious places of Catholic worship in the new century".5 The description itself hearkens back to modernist rhetoric of the 1920s that promoted the morally superior effects of abstracted machine-like architecture as an antidote to the tainted encrustations of traditional building. It is somewhat sad that anxiety about newness and cleanliness is being brought back to justify modernist churches.

Another Corbusian church has been developed since the 1990s by the Vatican. Built in the outskirts of Rome, the new church follows a Roman tradition of dedicating a major church for the fifty year cycles of the Jubilee.

For the new millennium, the Vatican selected American architect Richard Meier to design the symbolically charged Church of the Jubilee. Meier, who designed the famed "Crystal Cathedral" in Los Angeles, is well known for houses and museums based on Le Corbusier.6 His major work is the monumental Getty Museum, built during the 1980s and 90s in Los Angeles. The author of the Time magazine article on the cathedral at Los Angeles included a discussion of Meier’s Jubilee church. He proclaimed, "It says something about the triumph of modern church design that Richard Meier, an uncompromising inheritor of Mies van der Rohe [sic: it was Le Corbusier], was chosen by the Archdiocese of Rome to design the Church for the year 2000".7

Richard Meier has said that when designing in Italy he designs in the Italian tradition. If allusions exist between traditional Roman churches and the Jubilee church they are so abstracted as to be unrecognizable. When asked about such relationships, he has responded "it’s the scale".8

Meier has described the design as a "contemporary church, a church that has to capture the spirit of present times".9 Despite such yearning for the present, Meier quotes Le Corbusier’s fifty-year-old Nôtre Dame-du-Haut even more directly than Moneo did for the cathedral in Los Angeles. The church, called Dio Padre Misericordioso (Our Father of Mercy), was dedicated October 26, 2003.

One enters Meier’s church under a cantilevered canopy adjacent to the prominent blade of a vertical wall. This prow-like climax is similar to Nôtre Dame-du-Haut in that it anchors exfoliating planes that differentiate the interior. Unlike the solid mass of the thick walls at Ronchamp, however, Meier’s mural elements are thin and connected by sheets of glass. Many of the roofs are also made of glass and slope toward the wall parapets. (This detail may cause interior cascades from water funneled into the valleys.) A tower with a full register of bells is located to the right of the entry, emphasizing the asymmetry of the facade.

The Limitations of the "New" – and the Freedom of History

As a classicist, I believe in the value of emulating historic forms, so I do not object to the clear imitations of Ronchamp in these examples, but the debt these architects owe to Le Corbusier is most often ignored. By continually proclaiming the "newness" of these and other churches, architects and publicists take advantage of the public’s lack of awareness of architectural and cultural history. An unfortunate parallel exists to the "new and improved" hype of advertising and the broader culture that perennially calls for rejecting the past.

That Meier, Moneo and the other architects imitate the models they love is natural to mankind’s process of learning and doing by imitation. But limiting deeper exploration of how old buildings expressed Catholic culture does disservice to a two-thousand-year-old institution with vast examples of articulate, and by now well-documented and restored, precedent.

As a final example of the self-imposed limitation of expression, Brother Mel Anderson, spokesman for a design for a new cathedral in the Oakland diocese, has pronounced, "though we all admire the Gothic or Romanesque cathedrals of Europe, we wanted something new for the new century".

Brother Anderson follows prominent modernist art historians who believe that Gothic or Romanesque were fine for that time, but should never be resuscitated for today. This mantra is reinforced in the Time description of the Los Angeles Cathedral as having an "edgy silhouette [that] is both familiar and new, not a post-modern replica of Spanish Missions but a sophisticated recollection of them the excitement of the new, but it beckons you to the past".10

This makes for good copy, but it is very difficult to connect the words to the cathedral structure any more deeply than the standard touristic postcard that extols Any City, USA, as a mix of the new and the old. The Hispanic architecture of California’s Franciscan missions is a clearly defined phenomenon with a well-studied canon of architectural elements and structural maneuvers. There is no clear parallel between this tradition and the cathedral. The cathedral does have thick concrete walls tinted adobe color, but there is no deeper rapport because the architect restricts himself from imitating a formal canon.

An analysis of Moneo’s Our Lady of the Angels Cathedral in the professional journal Architectural Record presents a deeper analysis than Time magazine. The author contrasts Moneo’s approach to a classical response by stating "The church needn’t go quite as far as critic Michael Rose urges in his recent book Ugly as Sin to revert to highly traditional solutions somewhere to the right of Ralph Adams Cram. Replicating the old is not the answer".11

This comment could apply to churches designed by several colleagues and myself. Three of us submitted proposals for a chapel for Thomas Aquinas College in the northern sector of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. These designs illustrate how classical architects respond to designing a church today.

New classicism has developed since 1980 into a rigorous challenge to the principles and forms of late modernism. It emerged having different, but parallel, trajectories in Europe and the United States. Rejecting ambivalent and superficial uses of traditional elements, the architects made a commitment to learn the formal and procedural rules of this heritage. They delved into the deep tradition of architectural treatises and studied historic buildings to unlock formal understanding and to develop personal interpretations. Opportunities to practice forced them to learn how to adapt contemporary building practices to achieve their aesthetic goals. In doing so, this sharpened their understanding of the traditional architecture they loved.

Culture Enriched by Heritage

It is important to emphasize that in reviving this old heritage, new classicists do not nostalgically seek to recreate a past. Instead, they are looking to a future that is more inclusive, culturally rich, and intellectually stimulating than the current status. In their professional work they seek to conform to three objectives defined by the Greeks: to design functionally, strongly and beautifully. There are strong parallels, in the path my colleagues and I have experienced in the secular realm of architecture, to the experience of redefining the role of traditional Liturgy and discipline associated with the revival of the Latin rite and its training.

Thomas Aquinas College is focused on a traditional philosophy-based undergraduate education in Santa Paula, California. They have built a campus on a quadrangle with buildings that reflect Hispanic elements. The college administration has long planned to construct a chapel as a focal point on the quadrangle’s axis.

In 2000, Duncan G. Stroik, Michael G. Imber and I were invited to submit separate proposals for how the chapel might appear in plan and perspective. The requirements stipulated a longitudinal nave oriented toward a clearly defined sanctuary and the tabernacle. The client sought a building that would formally reflect dedication to traditions in education and the orthodox nature of the college’s spirituality and Liturgy. This program, and the choice of architects to compete for it, indicated a particular belief about what the role of the Catholic Church is at the turn of the millennium and how this should be manifested architecturally.

Duncan G. Stroik won the competition to design the chapel at Thomas Aquinas College. His design is modeled on a small number of Spanish churches in Mexico that abide by Italian Renaissance canons for façades based on temple fronts. His studies of the proportion of classical elements according to Andrea Palladio and of Palladio’s church façades have been modified in regard to the Hispanic context of the campus.

Michael G. Imber’s proposal responds to examples of the Romanesque tradition in Spain. (It is fascinating that in my experience, the Romanesque is the most frequently suggested reference point for how traditional Catholics think a new church should appear.)

My proposal for the Thomas Aquinas College chapel was a more vernacular interpretation of the Spanish and Italian traditions as built in Mexico.

The interior of all three proposals for the Thomas Aquinas chapel clearly distinguished the sanctuary from the nave. All three of us positioned the tabernacle to clearly terminate the view. The Aquinas chapel proposals reinforce the hierarchical distinction between the nave as a place for reverent laity and the sanctuary as a place where some kind of privileged access is required.

The hierarchical nature of traditional functional divisions within the Church reinforce one’s sense of liturgical decorum, and this is clearly called for in the Vatican II documents. Such demarcation of areas contrasts markedly with the more common "liturgical spaces" that stem from Ronchamp, where an auditorium always spills down to an altar platform, and the tabernacle is sequestered to a discrete zone. This second type of church interior has become ubiquitous in the United States. It has become the dominant interpretation of the Vatican II liturgical documents.

This style has often been justified as promoting "full, conscious and active participation" in the celebration of Mass, as if undifferentiated space naturally achieves consciousness for the laity. The environment that best facilitates genuine participation depends on cultural experience and training. The Ronchamp model is hardly the most effective in achieving this goal for the many Catholics who find it difficult to give themselves to "full and active participation" in worship within an informal building that lacks the traditional (and historical) shape of a church, either in functional or aesthetic terms.

A Church that Looks Catholic

Issues of cultural and spiritual identity were important for a diverse congregation in the appearance of a new church I designed for a Dalton, Georgia, parish. St. Joseph’s parish is located in a heavily Protestant region of the Appalachians. The initially small Catholic population grew to medium size as the region’s carpet industry attracted professionals. A huge influx of Mexican immigrants later came to work in the carpet mills and swelled the Catholic population. Both groups had a traditional bent to Liturgy and community life stemming from different cultures. Both wanted a church that looked "Catholic". I suggested the model of Post-Renaissance churches built in Rome during the Counter-Reformation period in the late 1500s. A particular model was the austere San Gregorio Magno in Rome that has a façade modeled on Early Christian structures as well as simplified Roman Renaissance precursors.

At St. Joseph’s in Dalton the large windows above the entry portico light offices, similar to the monastic arrangement at San Gregorio. Both the anglophone and bilingual groups at St. Joseph’s embraced the building’s appearance. The appearance and function of the building have aided full, conscious, and active participation in the Liturgy and parish life.

St. Joseph’s – Dalton, GA

Copyright © 2004

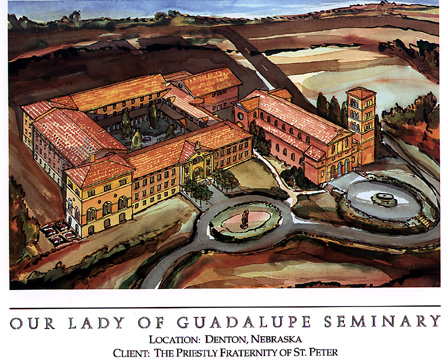

In non-parish settings, I have designed churches for the Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter near Lincoln, Nebraska and for a new foundation of Notre Dame du Fontgombault at Clear Creek, near Tulsa, Oklahoma. (Both illustrated below.) These churches must meet exacting functional and artistic standards. In the first instance, the building is the training ground for potential priests learning to revive the traditional Latin Mass. In the second, the monastic church is the place of lifetimes of intense liturgical focus for the Benedictine monks. In both cases, the exterior and interior appearance is a signal that must aid each group in reviving disciplines of traditional decorum. The spokesmen for both groups have requested that Romanesque models be the points of reference for new architecture. I think this is similar to the way in which Counter-Reformation patrons and architects sought to reconnect with early Christian models. Today, the Romanesque represents solidity, simplicity and religious vitality for traditionalist Europeans and some Americans. It is seen as coming from an ideal of monastic consensus to formulate discrete, well-proportioned buildings without striving for excesses; the last point is how the Gothic is perceived.

Copyright © 2004

Added to concern for the formal appearance, the clients are interested in the symbolic or mnemonic significance of number and proportion. The way in which the buildings will bring changing qualities of light inside also elevates the daily interaction between prayer, Liturgy and the natural environment. The design of these churches, therefore, can directly advance or inhibit full, conscious, and active participation in spiritual development. Iconographic depiction — as in paintings or sculpture — is not currently a significant factor in either project, but areas are being designated for eventual pictorial development.

The acoustical properties of the monastic churches are vital to the seminarians at Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Benedictines at Clear Creek, because both groups foster communal Gregorian Chant in their lives of prayer. Thus, contemporary methods of construction must promote what acoustical engineers officially call "a cathedral sound".

Copyright © 2004

From the exterior, each church must signal to the larger community that it is Catholic. The appearances of each, somewhat like the parish church at Dalton, must transmit the traditionalist approach of each religious organization. By striving to emulate historical achievements we seek to connect with many people who feel disenfranchised by churches built in the stylistic stream of Nôtre Dame-du-Haut at Ronchamp.

I would like to return to the debate between modernist and classical paradigms for new churches to focus on the factor that distinguishes enthusiasm for engaging with old architectural languages from the modernist’s lack of interest in articulate traditional elements.

"Décor of Custom"

The key to understanding why traditionalist and modernists see the role of historical influence differently is the concept Vitruvius called "décor of custom". Vitruvius was a Roman architect and military engineer who wrote The Ten Books on Architecture a little before the time of Christ’s birth.12 After the civil wars following the murder of Julius Caesar, he dedicated his treatise to Augustus to suggest how to rebuild Rome.

Vitruvius sought to revive the proportions and details Ionian architects perfected in temples between 300 and 150 BC. Vitruvius quoted specific ratios for the proportion of columns, moldings, and elements of detail. He called these quantities the symmetriae of Ionic architecture.

Vitruvius also presented concepts pertaining to methods of working, such as "décor of custom". This involved understanding why specific architectural elements should be employed exclusively for the Ionic system and not for other building types, like Doric or Corinthian. (For example, dentils, the tooth-like projections below the cornice, are appropriate for Ionic, but not for other columnar types.)

On a broader level, "décor of custom" creates a moment of truth for an architect, then or now, who must decide if he will employ culturally significant elements, not only appropriately, but if he will include them at all.

History, Custom — a Liberating Language for Today

Vitruvius conveyed many concepts about how architects work based on additional ideas from Greek treatises. In his introduction to the field of architecture, Vitruvius cites methods of drawing as well as conceptual thinking under dispositio. He is also concerned about economy and practical construction. Though these techniques are described in different terms today, each is practiced by all architects as a means for solving the difficulties of getting from an idea to an actual building.

Architects draw plans, elevations, and perspectives by hand or on the computer. This allows them and their clients to visualize possible solutions. Once decided, further drawings allow the concepts to become concrete for the contractor to build. All architects work with engineers and builders to execute a structure within the economy of available money and materials.

Modernist and classical architects equally employ these and other strategies Vitruvius outlined.

The exception is "décor of custom". This is because one must cross a threshold and break through the prohibition against using elements of a "language" when one considers what specific elements to incorporate into a plan. In the secular realm of professional practice, this "moment of truth" is akin to making a profession of faith that sets limitations on action based on thousands of years of accumulated wisdom. These limitations liberate one to a world with enriching possibilities for freedom and expression.

The era of prohibitionism and restrictions concerning "décor of custom" should be over, but the question is far from being resolved.

My fellow classicists and I believe that architects should utilize Vitruvius’s principle of "décor of custom" with the goal of achieving wholeness in new buildings to serve the Church. We believe that it is time to open the interpretation of the Vatican II documents of Sacrosanctum Concilium so that the full, active, conscious participation can involve a sense of continuity with Catholic tradition, not a rejection of it. Recent questioning of the tenets of Modernism allows us to respond to these profoundly important directives with a renewed sense of the relevance of the breadth of Catholic tradition during the 21st century.

As patrons continue to emerge, classical architects will be employed in the service of the Church because they can speak its tongue. Liturgists and architects must seek ways to encourage that language to be spoken again. New churches will have a variety of expressions founded in the rich heritage of particular models. They will solve many functional and structural problems with logic, interest, and sophistication.

The new generation of churches will engage the emerging classical painters and sculptors who can create religious art that is both readily accessible and spiritually challenging. Finally, they will employ an articulate language of architecture and related iconographic expression to reanimate the experience of "going to church" in both intellectual and spiritual senses.

***

NOTES:

1 Sacrosanctum Concilium, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council, December 4, 1963. Available on the Adoremus web site, www.adoremus.org, Church Documents section.

2 Kenneth Frampton, Le Corbusier, Architect of the Twentieth Century (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002) 38-53.

3 David Watkin, A History of Western Architecture (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2000) 651-652. The text describes "… the pilgrimage chapel at Ronchamp, with reinforced concrete form concealed behind billowing neo expressionist forms. The strange poetry of this unique sculptural building exercised little direct influence…"

4 Le Corbusier (Jeanneret-Gris), The Chapel at Ronchamp (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1957).

5 Richard Lacayo, "To the Lighthouse", Time, September 2, 2002, 64.

6 Kenneth Frampton and Joseph Rykwert, Richard Meier, Architect: 1992-1999 (New York: Rizzoli, 1999).

7 Lacayo, 66.

8 Account by Italian architect Carmine Carapella of a lecture to architecture students and the public and conversation afterward, Spring 1998, in Rome about Meier’s project for the Ara Pacis and the Church for the Year 2000.

9 Lacayo, 66.

10 Ibid., 64-65.

11 Suzanne Stephens, "Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels", Architectural Record (New York: McGraw-Hill, November 2002) 132.

12 Thomas Gordon Smith, Vitruvius on Architecture (New York: Monacelli Press, 2003).

***

Thomas Gordon Smith is professor of architecture at the University of Notre Dame. He is the author of Vitruvius on Architecture (New York: 2003 The Monacelli Press). This essay was originally presented to the 2002 conference of the Centre International d’Etudes Liturgiques (CIEL), and appears here (slightly edited) with the author’s kind permission.

Professor Smith’s web site affords descriptions and illustrations of other works:

www.thomasgordonsmitharchitects.com

Return to AB April-May 2004 Contents

***

*