Online Edition

– April – May 2004

Vol. X No. 2-3

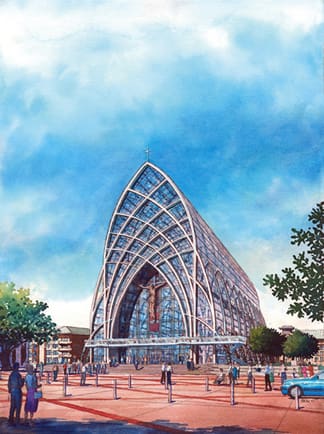

Ave Maria University Reveals Plans for Giant Church

As part of a plan for a new campus and town in southern Florida, Ave Maria University recently unveiled detailed designs for the centerpiece building of its community — a church.

Described by university officials as a "soaring glass, steel, and aluminum structure", the 60,000-square-foot mega-chapel calls for three thousand tons of structural steel welded and bolted together. Clad in glass and aluminum, this filigree structure will loom enormous on the landscape at 150 feet tall. The chapel is set to be the largest Catholic church in the United States. But rather than creating a

pièce de résistance

that would symbolize the promising aspirations of the newest Catholic university in the country, the architects have given birth to what could, instead, become an embarrassing eyesore.

Decidedly abstract and modernist in its architectural vocabulary, the proposed design markedly breaks with the historical continuity of two millennia of Catholic church architecture. Yet far from being a

new

"break", the huge chapel’s retro style of the 1960s is but another example of the persistent disregard for history that has characterized most church architecture of the past half-century: in other words, outdated "novelty".

Moreover, the proposed design is inconsistent with the stated goals and Catholic commitment of the academic institution it represents; and it fails as a worthy house of God for the Catholic people.

Creating a "worthy house of God" is, of course, a tall order, for any architect. Fortunately he has at his disposal more than 1500 years of his craft on which to reflect. When he turns to the Catholic Church’s great architectural heritage, he discovers that from the early Christian basilicas in and around Rome to the Gothic Revival churches of 20th-century America, the same canons are observed in the design of successful Catholic churches, even if they are expressed differently in every epoch.

Churches whose designs grow out of the past two millennia of ecclesiastical patrimony identify themselves with the life of the Church throughout those two thousand years. By their continuity with the history and tradition of Catholic church architecture, such churches also manifest the permanence of the Catholic faith.

This continuity necessarily means that authentic Catholic church design cannot spring from the whims of one man or the fashion of the day. A successful Catholic church building is a work of art that acknowledges the previous greatness of the Church’s architectural patrimony: it refers to the past, serves the present, and informs the future.

Modernist Inspiration, Antecedents

Although the proposed floor plan for Ave Maria’s chapel is vaguely reminiscent of a classic basilica-style church (as much can be said of the recently completed Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles), Ave Maria’s proposed structure otherwise breaks with the venerable history and tradition of Catholic church architecture prior to the iconoclastic thrust of modernism that dominated most public buildings in the late 20th century.

Even with its abstracted steel "buttresses" and aluminum pipe "columns", the church pays respects not to the timeless patrimony of the Church throughout the centuries; rather it clumsily tips its hat to the missteps in church architecture taken over the past half-century, with particular reverence (via superficial imitation) paid to several non-Catholic modernist chapels — especially the non-denominational "Thorncrown" chapel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

In 1981, architect E. Fay Jones won several awards for his Thorncrown design. The modest structure, a filigree of wood timbers and sheathed in glass, is tucked away in the woods of the Ozarks. The criss-crossing light wood frame recalls the surrounding trees, and the general feel one gets from sitting in Thorncrown is communion with nature — the primary guiding principle of that architectural project.

E. Fay Jones, as Ave Maria officials have noted, was a one-time apprentice to Frank Lloyd Wright, often hailed in this country as "the father of modern architecture". Ave Maria founder Thomas S. Monaghan is a devotee of Wright’s "prairie style" architecture — typically long, low structures that hugged the Midwest prairie; extant designs of the other Ave Maria campus buildings consciously reflect this prairie style influence. In fact, Mr. Monaghan, the proposed chapel’s primary benefactor, once owned a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and is a significant collector of Wright artifacts, which have been displayed at the Renwick Museum and elsewhere.

It will come as little surprise, then, that Ave Maria’s chapel design also reflects the Wayfarer’s Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes, California. Built [by Lloyd Wright, son of Frank Lloyd Wright] for a Swedenborgian congregation, this structure of redwood frame, glass, and blue tile achieves a unique effect because of the vista of sea, sky, and hills within the worshiper’s vision. It is well known that Wright publicly rejected the European heritage of churches, disdainfully referring to them as "sepulchers". Lloyd Wright asserted that his chapel design embodied the philosophy and theology of the Swedenborgian Church — with which Wright (along with Johnny Appleseed) said he identified. The Swedenborgians emphasize the harmony between the natural world and the human mind. Translation: the Wayfarer’s Chapel, at the service of pantheistic naturalism, was designed for one to contemplate nature, which can be easily observed through the glass-skinned structure.

Glass Houses

Both the Wayfarer’s Chapel and Thorncrown are modest wood-frame structures situated in forests. Ave Maria’s design is neither modest nor wooden — nor is it to be built in the woods. Rather, in the proposed design for Ave Maria’s chapel, these two modernist precedents are reworked in both size and materials to resemble two other famous chapels: the non-denominational chapel at the U.S. Air Force Academy near Colorado Springs — massed like a phalanx of fighter jets shooting up in the sky, the glass-skinned church looks like it comes straight from an origami book; and evangelist Robert Schuler’s "Crystal Cathedral" in Los Angeles, one of the earliest "worship spaces" in this idiom.

Ave Maria’s proposed church is perhaps most reminiscent of Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, the enormous hall designed to house London’s Great Exhibition of 1851.

Constructed entirely of cast iron and glass, the Palace was the largest structure to be built of prefabricated units up to that time. It is generally recognized by architectural historians as the forerunner of the industrial construction that has produced many of the unseemly behemoths of the twentieth century. Paxton was a horticulturist, landscape gardener, and greenhouse architect. Not coincidentally, his masterpiece resembled a giant hothouse. The same could be said of Ave Maria’s proposed church.

Considering the blistering heat and humidity that characterizes the climate of southern Florida throughout most of the year, a glass-skinned hothouse is about as impractical as it gets.

It’s possible that, through heroic feats of modern mechanical engineering, the voluminous interior could be cooled down below a reasonable ninety degrees throughout most of the year. Modern glass might be able to mitigate the overbearing heat build-up and be made strong enough to resist any wind load. But what kind of glass resists bird droppings, dirt and water spots? As one Ave Maria supporter has noted, "if we can send men to outer space and [usually] not have them burn up or freeze, we certainly have materials which make this church design feasible".

Nevertheless, the time and expense spent on rigging modern technology to correct all the problems created by the Goliath hothouse design might be better spent on producing a beautiful and functional chapel to begin with. After all, the NASA space development program has no small price tag. The same might be said of mechanically cooling the 150-foot high, 60,000 square foot building — a voluminous interior indeed.

Size and Symbolism

Even if the architects decided to scrap the idea of using glass, and instead sheath the steel and aluminum filigree with something like slate shingles, the mega-chapel’s shape — and especially its size — will still present a monumental practical and technological problem, leaving aside aesthetic and religious considerations.

To be sure, Ave Maria is emphasizing the superlative size of its proposed church. According to a March 24 press release, university officials stated that the new chapel "will have [the] largest seating capacity of any Catholic church in the country" as well as "the largest crucifix in the world" hanging on the front façade, measuring sixty feet high.

Architects and university administrators evidently believe that bigger is better in all things. More often than not, however, bigger really is just bigger — or worse.

The Ave Maria design provides a case in point: There is no more fitting Christian symbol for the façade of a Catholic church than the crucifix. In this day, when liturgical fad-mongers seek to suppress the sign of the cross, a design featuring a prominent crucifix ought to come as a welcome relief. But when the symbol gets blown so overwhelmingly out of proportion, it too easily becomes a pietistic parody — and risks undercutting its intended message. For example, in a report on the proposed Ave Maria chapel design, the Salt Lake Tribune ran a headline that read: "Students at new college to be greeted by giant Jesus".

Does the inflated size of such a crucifix say more about the crucifixion of Christ, or about the people who built it?

During the construction of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles (1998-2002), Cardinal Roger Mahony frequently emphasized its size. He, too, wanted the "biggest Catholic church" in the country, so the floor plan was designed to be ten feet longer than St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, and it provides more seating than its East Coast counterpart. But because Los Angeles is the largest archdiocese in the country, serving well over four million Catholics, the size of its cathedral (its maximum seating capacity is 3,000) is obviously justified. Although this modernist cathedral has been criticized for many reasons, objection to its size is not one of them.

But what justifies the sheer "bigness" of Ave Maria’s chapel? An obvious question arises: Why would a tiny new Catholic school with 122 students (or even 5,000) on a campus in the remote swamplands of Florida need — or want — to accommodate 3,300 people?

"This will be the place of worship, not only for students, faculty, and staff, but also for their children, their families and their friends in the town", said Father Joseph Fessio, chancellor of Ave Maria University. It’s a "meeting place between the campus and the town", said Ave Maria’s president, Nicholas J. Healy.

According to the university, it is planned that 20,000 Catholics will eventually live in the budding town of Ave Maria, which will surround the campus. All of them, it is reasoned, will want to go to Mass every day — therefore the size of the campus chapel is justified. But that reason flies in the face of the way the Catholic Church’s parochial system works and has always worked in this country and in most others.

When new towns are founded or when cities grow, the local bishop is charged with caring for the influx of new Catholics. Typically, he will do this by founding new parishes. Each parish builds its own campus — usually including a church, a rectory, and perhaps a school.

The largest parishes in the country rarely have churches that seat even half as many people as the Ave Maria chapel plans to provide — nor would it be desirable. Twenty thousand Catholics served by a single parish under the same pastor could create a pastoral nightmare — no matter how big the church building might be.

Wouldn’t it make much more sense for a fledgling school like Ave Maria to build a well-designed, modest-sized chapel for its community, one that would accurately reflect the university’s Catholic nature?

Architects who understand the historical patrimony of the Catholic Church could deliver a fitting and dignified design, one that identifies with the life of the Church and with the local culture. Tiled roofs and thick stucco walls might respond to Florida’s climate; sacred imagery could recall Florida’s heritage of Hispanic Catholicism.

Ave Maria’s chapel deserves to be universally and unmistakably Catholic in spirit, character, and personality.

Thus far, Ave Maria and its architects have missed a tremendous opportunity: belltower, steeple or dome could beckon from afar; statuary, sculptural reliefs, frescoes and stained glass could evangelize, teach, and catechize. The entire sacred edifice could lift the mind to God. It could be a beautiful and timeless work of art built for eternity.

Alas, the current proposed design does none of this. Ave Maria: back to the drawing board!

****

[NOTE Update: See Michael Rose’s

article

"An alternative proposal for Ave Maria Chapel" and a "slide show" of

designs for the new town, campus and chapel

, a project of Notre Dame architecture students, on

web site.]

****

Michael Rose, author of

Goodbye, Good Men

, and two books on architecture,

Ugly as Sin and The Renovation Manipulation

, holds degrees in architecture and fine arts. He is the editor of

cruxnews.com

.

***

*